▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒ Collective work on the DoU hypothesis and the zine (in alphabetical order): Zeynep S. Akinci, Zahra Behrouzmoghadam, Carla Boserman, Maria Cifre Sabater, Tomás Criado, Fernando Domínguez Rubio, Adolfo Estalella, Ricard Espelt, Elena García Nevado, Rubén Gómez Soriano, Anna Koskinen, Daniel López, Ali Maddahi, Isaac Marrero Guillamón, Francisco Martínez, Marta Morgade, Davoud Omarzadeh, Santiago Orrego, Irra Rodríguez Giralt, and Enric Senabre.

Essay: Tomás Criado.

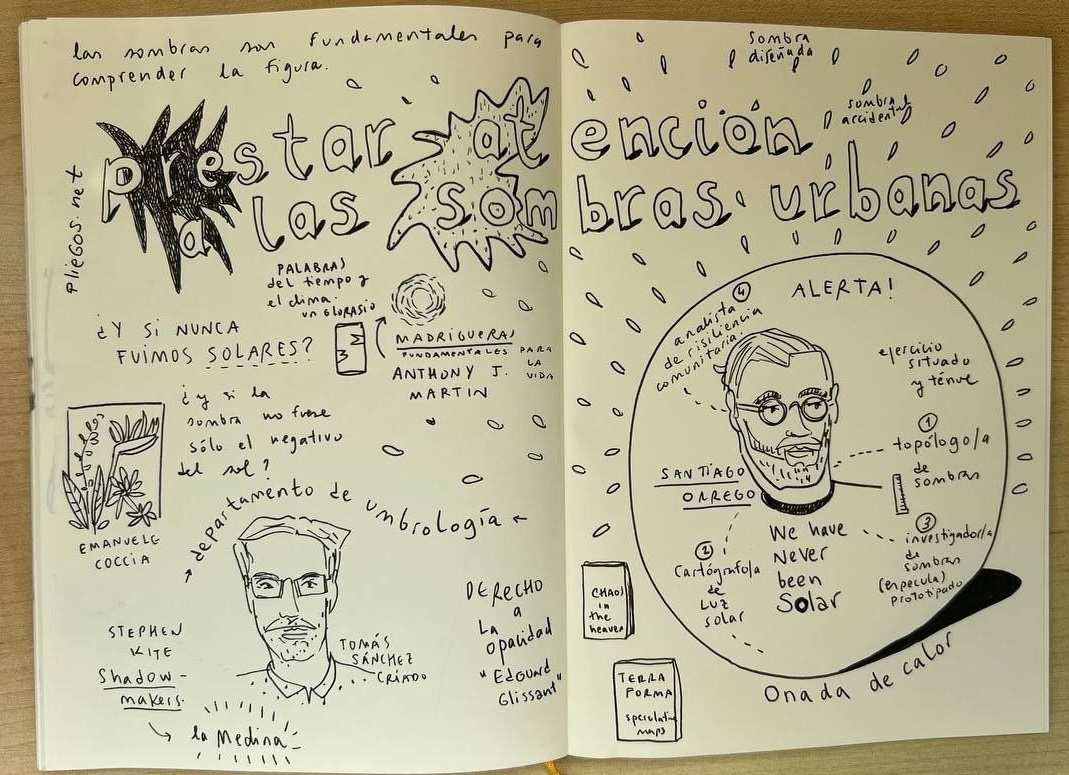

Graphic report of the event: Tomás Criado and Santiago Orrego.

DoU zine upgrade: Santiago Orrego.

This number was curated by Francisco Martínez and Elisabeth Luggauer.

▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒

Cite this article: The Department of Umbrology. 2024. “Prototypes for a Department of Umbrology.” Tarde 8 (Nov – Dec). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/ACF64

How could we transition from a dangerous modernist ‘solar urbanism’ [1] to the renewed hope in the urban powers of shade? This transformation is far from just material or technical one; it also requires culturally symbolic and everyday practical undertakings. However, to achieve this, perhaps there is no other way around experimenting with speculative political practices and collective formations, where ethnography might still play a relevant role: not just as a documentary practice but an interventive one. A possible avenue to try out new forms of ethnographic relevance could be to draw inspiration from artistic practices searching to probe new ways into the contemporary climatic mutation in its complex local expressions.

As suggested in Tarde’s number 6, The City of Shades – the first in a trilogy on urban shades – we could follow the trail of the guided walks proposed by Los Angeles Urban Rangers or the immersive protocols of experimental politics of the Crisis Cabinet of Political Fictions [2]. Their works could be of great relevance to go beyond an attempt at undermining the practices of existing institutions. In fact, at a time when reclaiming the social state as a crucial infrastructure accompanying and sustaining experimentation with the forms of personal and collective protection might be needed, the task might be more akin to what legal activist Radha D’Souza and artist Jonas Staal stated when proposing their Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC):

“For art to have emancipatory significance, it must go beyond mere questioning and deconstruction, and learn to retool statecraft’s arsenal to construct alternative popular institutions” [3].

Taking this thread, perhaps what is needed in times of a deep climatic mutation and growing extreme urban heat is to propose an alternative popular institution of that kind, as a parasitic companion to the work of existing civic actors and administrations. As put forward in Tarde’s issue #6 we could unfold a Department of Umbrology (DoU) in our urban territories: a space where to equip a new kind of professional of this strange discipline imagined by writer Tim Horvath, as well as a crossroads of knowledges and practices, bundling together those interested in the inquiry on and politics of urban shades.

But what would be the relevant knowledges and the concrete practices that this department, however fictional or speculative, might need to foster? First of all, it would need to gather people devoted to understanding things like: the social and material complexity of shades, the multiplicity of actors and assemblages constituting them; the practices of generating shade, by and for whom; or the forms of sociality that they allow as regions or territories of care, attending to their temporalities, their rhythms, and their spatial dramaturgies. Come what may, its first mandate would be to create the conditions for all this to happen.

Even if we imagined it to be a flexible collective of sorts – perhaps even summoned anew for every issue, articulated around yet-to-be-defined requests or mandates, and devoted to exploring the wide gamut of mediational possibilities ranging from civic or artivist protest to para-institutional endeavors – to grant it some reality we needed a setting, as well as a series of practicable ways for people to imagine this. Our current issue seeks to document a first attempt at doing this.

Testing the DoU hypothesis in a sheltered environment, I: Background

The concrete setting to materialize this speculative scenario took us around six months of on-and-off preparatory work. It happened in and around an open 5-day workshop, The City of Shades, in Barcelona on June 17-21, 2024 [4]. Organized in collaboration with Santiago Orrego, the workshop was backed by my own Ramón y Cajal research funds and a small amount of funding and promotion for the Architectural Weeks of Barcelona. The workshop was put together in collaboration with the City of Barcelona’s Climate Change and Sustainability Office and BIT Habitat, a foundation from the municipality whose mandate concerns deploying internal innovation mechanisms within the city hall and fostering the city’s innovative ecosystem to face municipal challenges.

I have been formally collaborating with both areas of the city council of Barcelona since July 2023, when they launched an architectural contest to prototype temporary public space shade solutions for the hot season. The contest wished to make emerging solutions unavailable in the market, responding to a main need detected by the municipality’s public officers: although, in their view, tree shade should be the main way to go, even in the midst of the worst drought of a century, certain urban configurations and regulations make it impossible to plant trees or other forms of greenery. Particularly (1) big open places with underground heavy infrastructure, such as transportation pathways or car parks, (2) small streets where fire regulations would not allow tree planting, and (3) playgrounds due to safety regulations concerning their pavements and zonification. The focus on these three spatial problems, as well as a desire to have re-usable, scalable and modular solutions, became the main prerequisites of the contest.

The ‘temporary public space shade’ challenge serves to develop one aspect of the ‘shade plan’ conceived in the City Council’s Climate Plan 2018-2030, an ambitious series of adaptation and mitigation interventions, amongst them a wide portfolio of measures to tackle urban heat [5]: ranging from public space interventions (climate shelters, shade infrastructures, bioclimatic itineraries) to attempts at decarbonising building cooling, incentivising aerothermal solutions centring energy poverty. All of this is part of a crucial agenda of the municipality for environmental justice, foregrounding its concern for ‘vulnerable populations’, like children, older and disabled people. Indeed, after increasingly scorching years, with every summer bringing sky-rocketing temperatures, Barcelona’s humid heat is one of the city’s main public concerns.

For the challenge, three consortia were selected by a committee of technical experts who valued how well the initial ideas might develop over a year into good-enough technical projects to respond to the contest’s challenges [6]. The consortia are of a rather mixed nature, comprising companies and architectural studios, cooperatives of architects and woodsmiths, or agricultural greenhouse providers, and a network of cooperative architects and social cooperatives. They were awarded 100 000€ to produce an idea that would be implemented with the advice of the relevant urban planning areas of the municipality, installed in given public spaces, and monitored in the next hot season. The incentive for this prototyping endeavor is that later, they could define the municipality’s calls for tenders for future urban shade products and establish a business model selling them to the public sector.

Since July 2023 I have joined as a peculiar fly-on-the-wall ethnographer the technical mentoring meetings, where the projects’ makers met with different public officers from relevant municipal areas – usually, engineers and architects by training – in charge of monitoring any new addition to Barcelona’s already packed public space. Interestingly, as the installation phase approached, I was asked for advice.

Although our formal collaboration agreement doesn’t include any payment for services, all parties became interested in having my views on how to approach the ‘social monitoring’ of the projects, a requirement from the municipality. It accompanies a more technically-developed ‘climatic monitoring’ (measuring temperature, humidity, shade coverage, etc.). Each project will need to study their own prototype and produce accounts of societal acceptance and use, as well as of thermal comfort [7]. Ever since, I have been informally suggesting and advising how to engage in the design of their surveys (sampling, data-gathering techniques, etc.) or discussing more or less experimental cartographic approaches to study spatial use: flow movements and permanence.

Even if thinking on the relations between shades, architecture, and heat practices has proven an extremely creative conceptual exploration from the onset, my ethnographic work remained confidential and tied to an activity of minute-taking: filling up pages and pages of a notepad to remember rather dense technical details. This is where the idea of a collective and public-oriented Department of Umbrology, where to inquire and discuss intuitions on the urban life of shade with others, became an interesting hypothesis to explore and experiment with forms of ethnographic relevance in the vicinity of all the other technical actors I have been collaborating with: not treating ‘the social’ as a closed category in advance (what the material or the climatic is not, the human factor), nor invoking it after the fact (providing sanctioning takes about technology acceptance) but rather evoking its emergent, everyday and ongoing creative process. To do this, we needed to imagine ways in which ethnography could come to matter: hopefully opening up what the social might mean in different shady locations, enabling more nuanced takes on the complex social and material life of shades and their forms of urban care.

i. Testing the DoU hypothesis in a sheltered environment, II: Producing a collaborative workshop

Testing ‘what a DoU might be’ was the inspiring idea behind The City of Shades workshop. A 5-day event, open to like-minded interdisciplinary people coming from the arts and humanities, the social sciences, and the design and architectural disciplines, with mandatory prior registration to screen who was interested and be able to create relevant synergies when attempting to articulate an exploratory collective research space like this. Sensing the organizational burden would be too much for us to carry the conceptual weight of the workshop, and in a spirit of collective speculation where many more views are needed, we additionally invited as mentors six colleagues from the arts and the social sciences working on experimental ethnographic approaches and with an artistic sensitivity to inquiry, who would push us to take it seriously or contribute to expand it beyond what we had imagined.

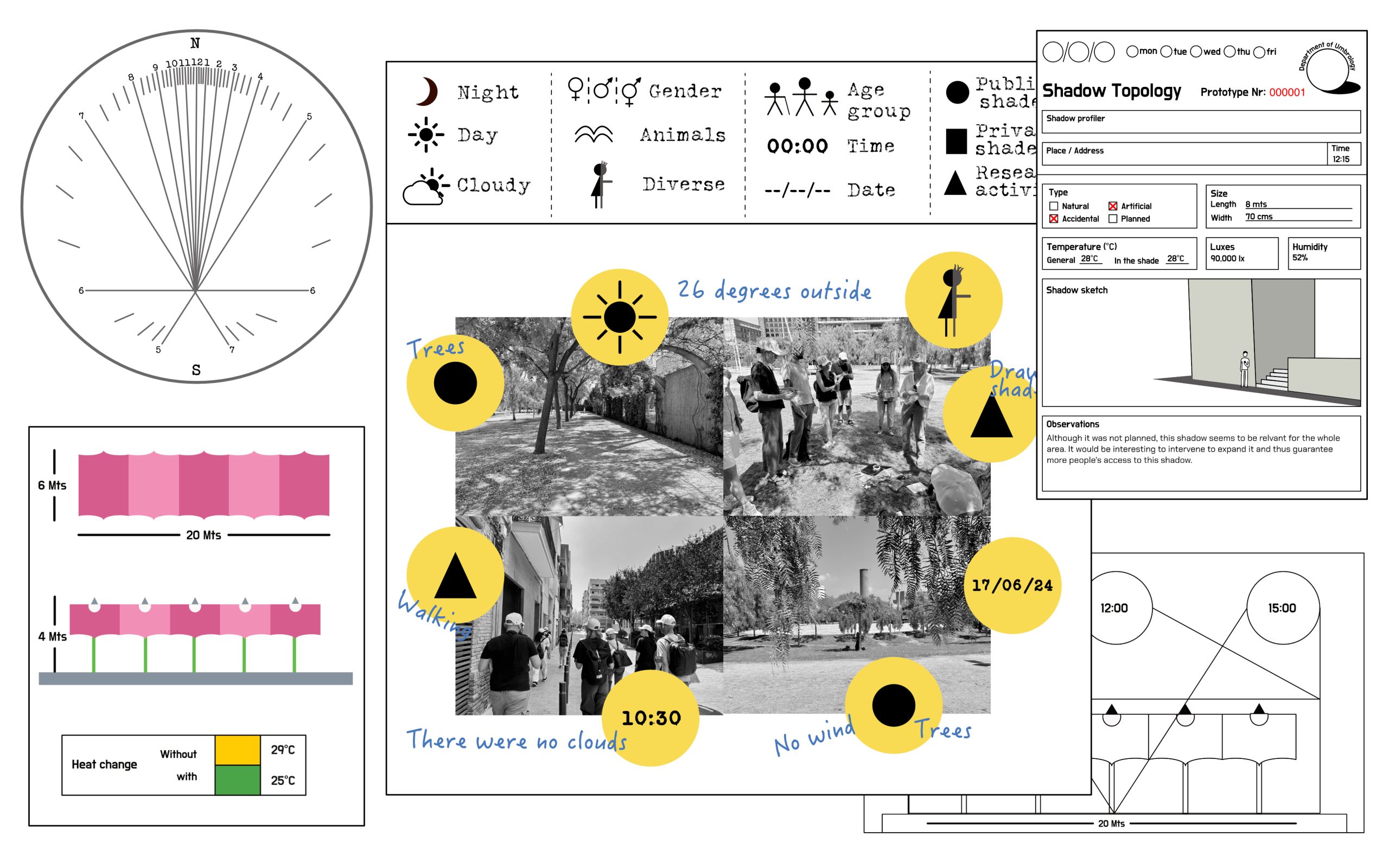

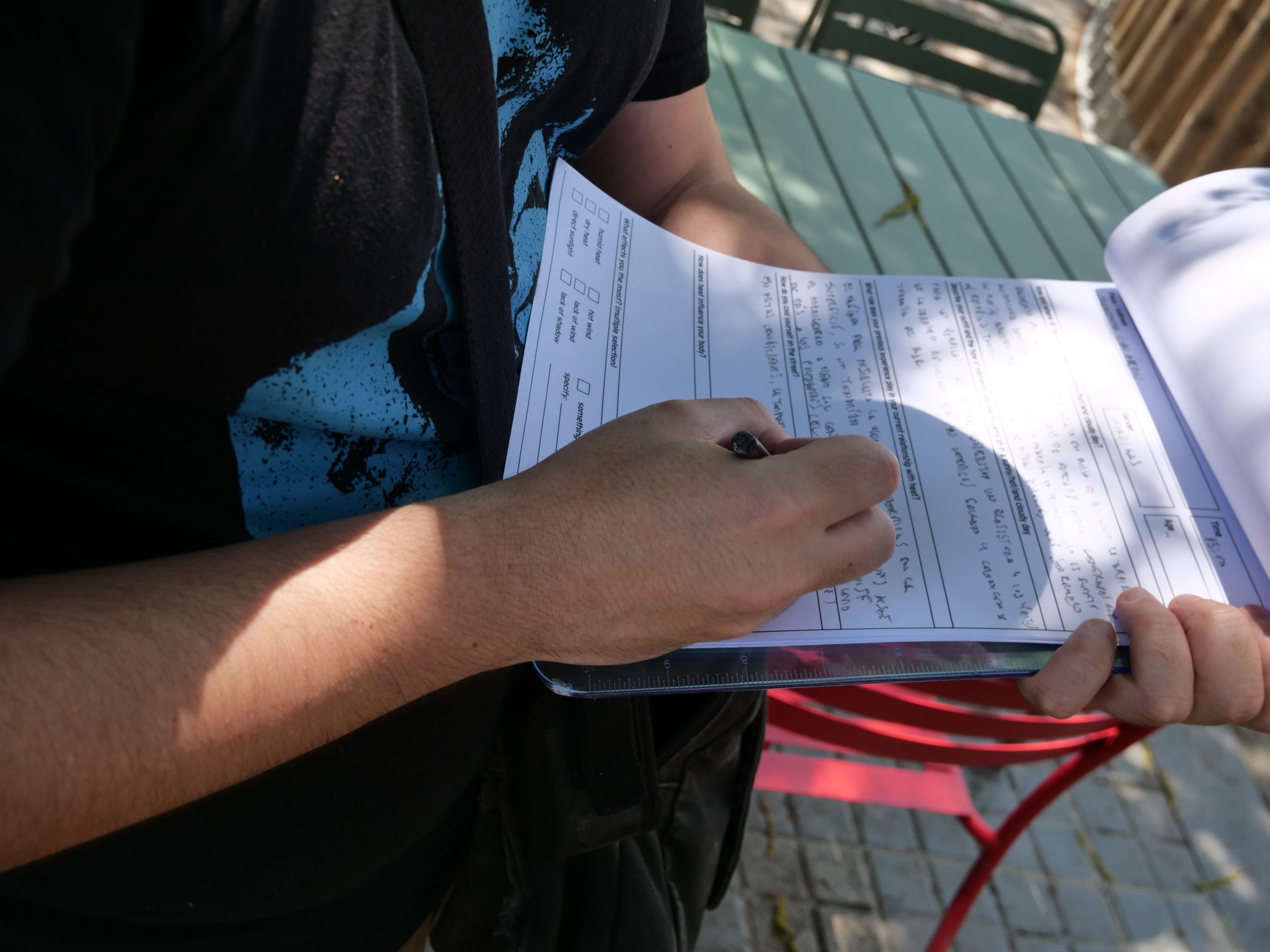

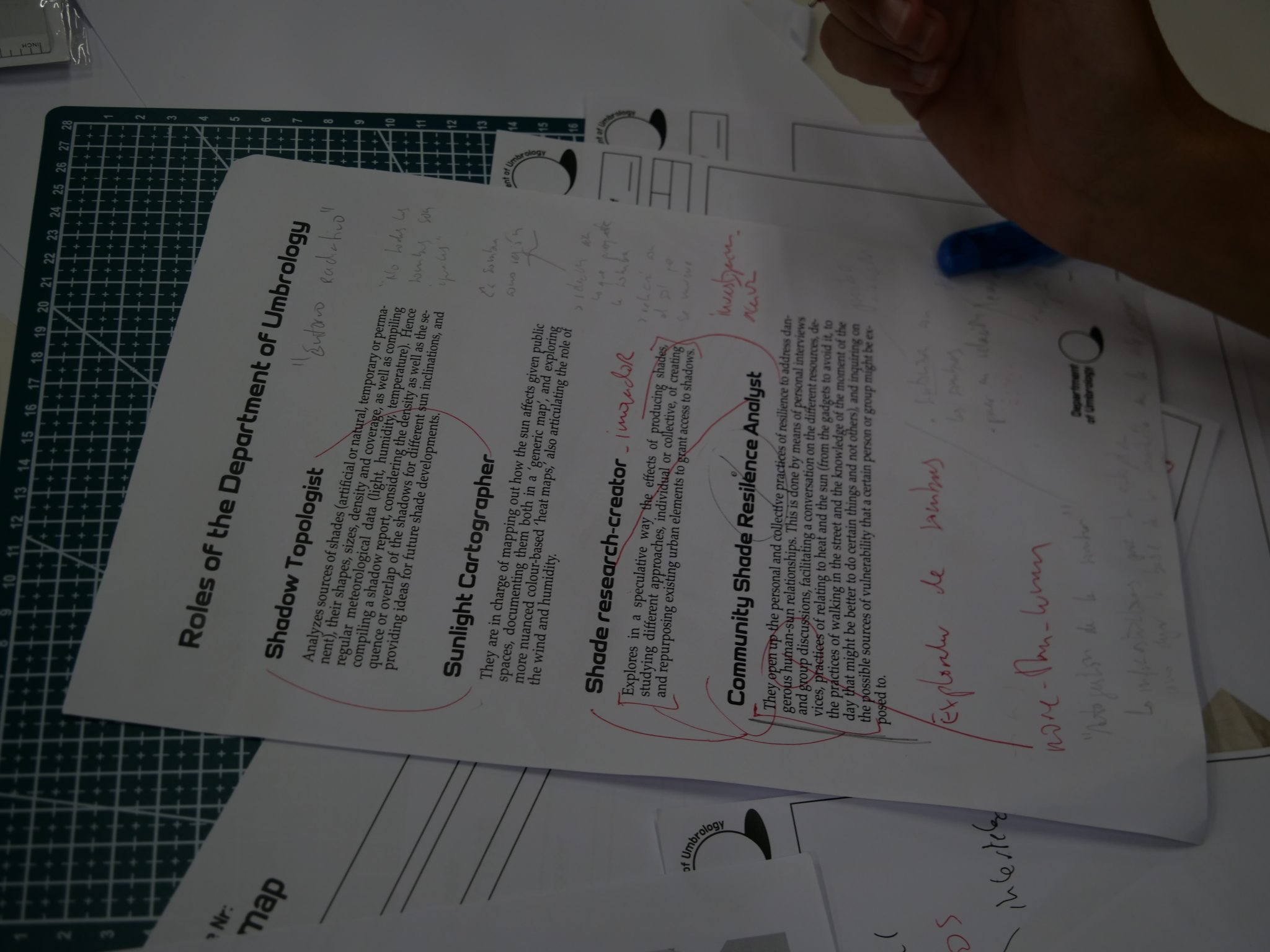

To render this practicable, we imagined umbrologists would require a series of roles, such as: (1) Shadow topologist, (2) Shade research-creator, (3) Sunlight cartographer, and (4) Community Shade Resilience Analyst. For each of these roles, we provided a small description and designed a series of specific forms, enabling the DoU to be imagined as a department of sorts: working ‘in the shadows’ of real ones, re-signifying what ‘shadowing’ tends to mean in common ethnographic parlance [8]. We also created a logo, a website, and baseball caps each of the participants could wear to protect from the scorching sun in our urban explorations as a way to enforce an idea of corporate identity and to become noticeable when moving around. The materials gathered in Tarde’s issue 6 and its zine were the main outcome of this preparatory effort. Indeed, the long essay was the discursive opening of the workshop, and the zine contained some of the forms we conceived and tried out.

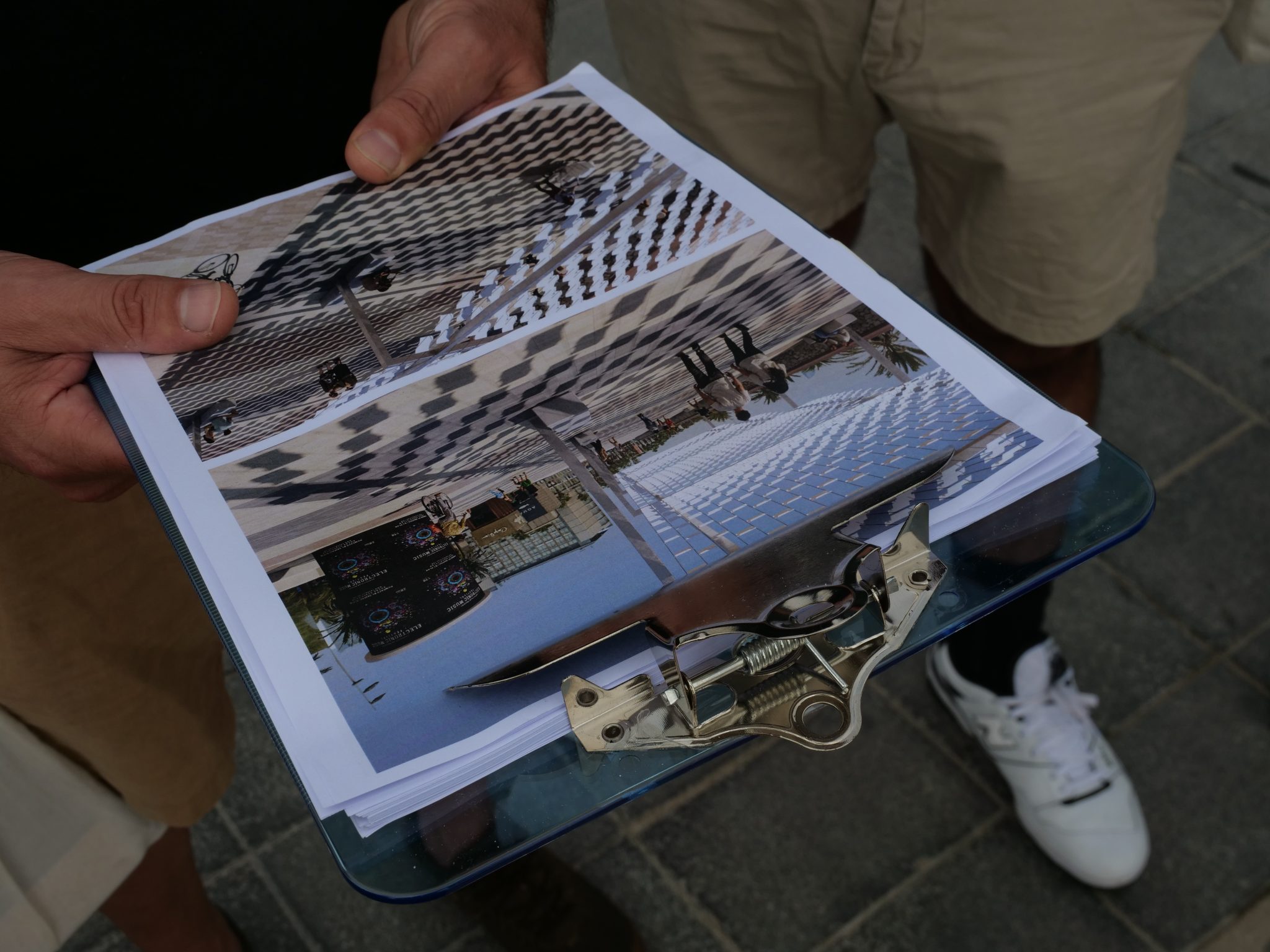

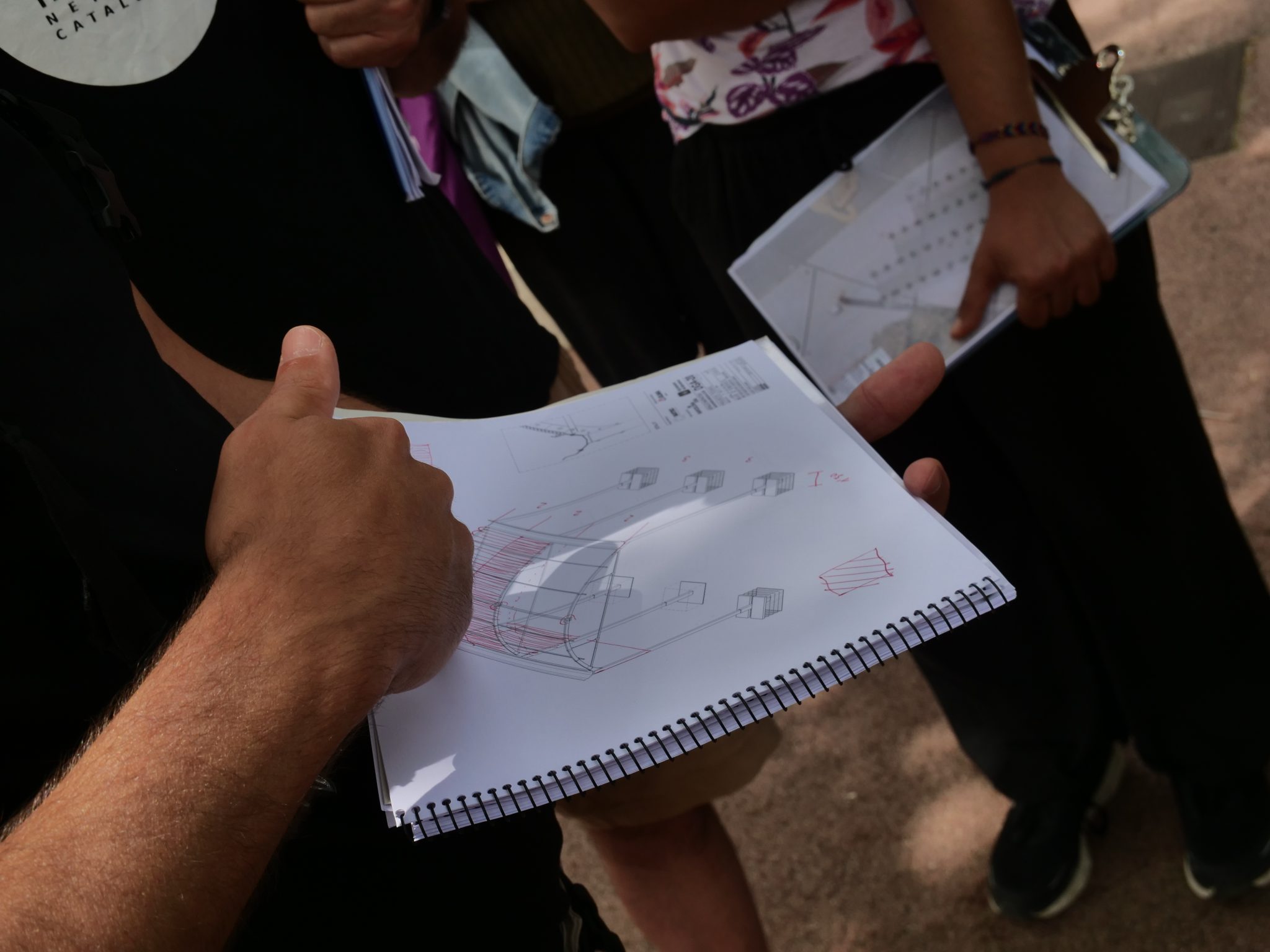

We didn’t imagine this kit to be more than a first workable version, something enabling us to plunge into the problem and its conundrums more quickly, helping people have something to work with when thinking on shades for the first time. Our aim, thus, was to put to a test these bureaucratic forms undertaking a series of guided walks (around the Poblenou district of Barcelona, where the workshop venue was located; and monographic visits to the future sites where the municipal shade prototypes were going to be implemented, meeting the projects). We wanted to do so with the objective of later engaging in the hands-on redesign of the roles and forms of what a DoU could be, inspired by lectures, presentations and hands-on activities.

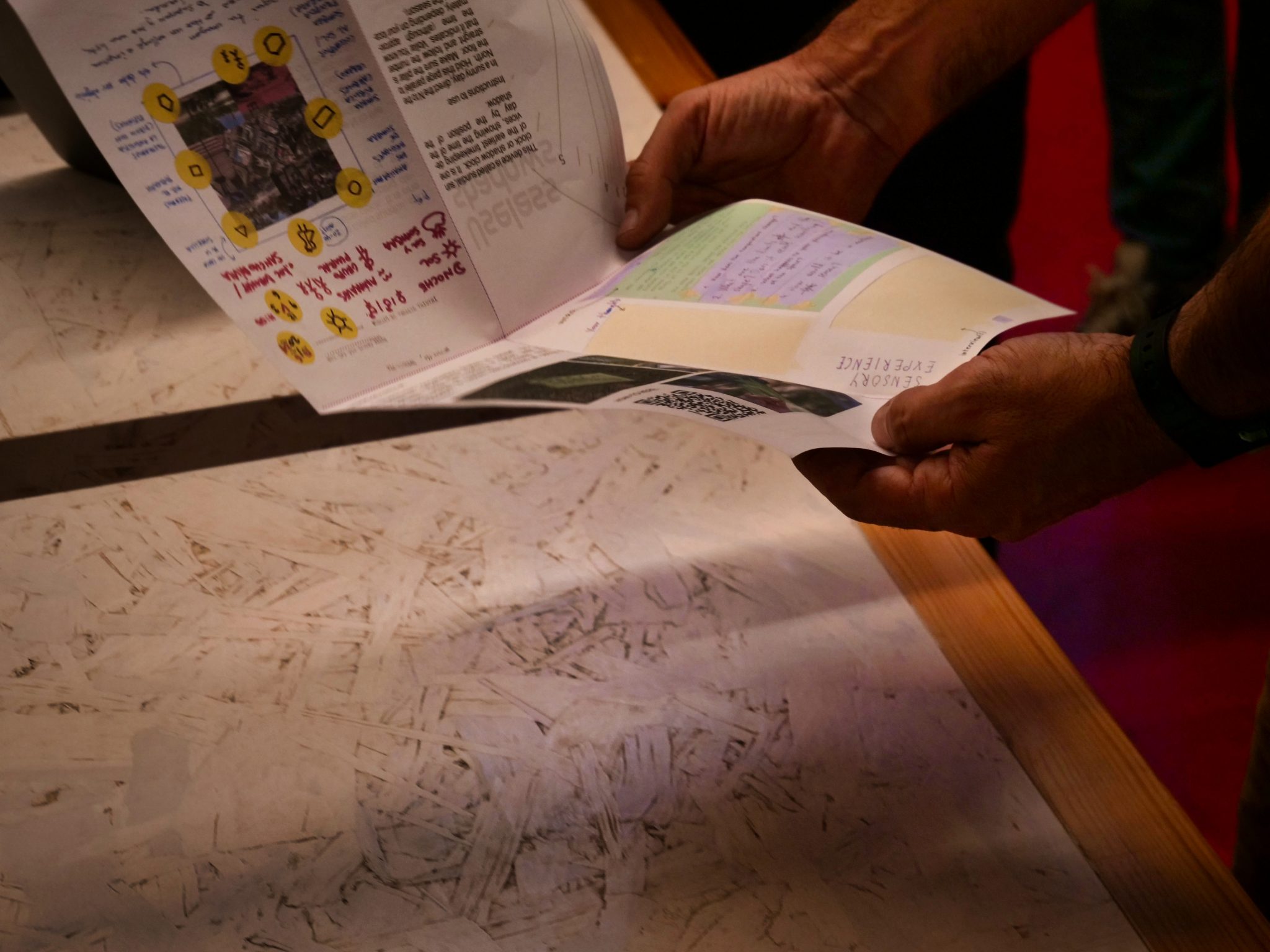

With the help of the mentors and a core group of 15 people who had registered – mostly from social sciences and architectural backgrounds – and the fluctuating assistance of people from the architectural contest, we had the immense luck to explore the possible research devices and mandates for the DoU. Our learnings were summarised on-site: the workshop ended with the production in less than 8 hours of a fanzine, with the help of the open source collective PliegOS (our thanks again to Enric Senabre and Ricard Espelt for their work on this!), specialized in alternative forms of public documentation of events [9]. This raw and wonderful collective zine formed the backbone of the ethnographic kit for the study of urban shades you can now download in this issue. The only upgrade has been slightly polishing the language and developing aesthetic continuity between the different parts.

ii. Learning to become umbrologists under the scorching sun: Documenting the workshop

Sweating over our cards, on different walks we learned to think about the urban inclinations of the sun, to relate to trees and plant coverage, to draw shadows with solarized spinach paper, to distinguish shade’s private contours (in the form of bars and terraces) from shady public infrastructures, to understand the relevance of broadening our view beyond the human (exploring an ethology of shades!), and to find ways to gather experiences of urban shades.

Our workshop took place mostly in the Sant Martí district of Barcelona, where the Poblenou neighbourhood is located. This is where I live and work, and my previous experience walking around with my daughters informed the selection of the places. But we also ventured beyond it when visiting the places where the municipality’s shade prototypes were to be emplaced and installed. This experimental journey also took us to the seafront of Barceloneta, then to the immense gap between large buildings of the Maresme-Forum over one of Barcelona’s main ring roads, or to the highline of the Sants district, created over the transportation box that the underground and commuter trains use to traverse the city.

As novice umbrologists, these endeavors enabled us to probe into the true power of urban shades, which also swallowed a measuring briefcase from the municipality without leaving a trace in one of our visits. In the final session, prior to working on the closing zine, I attempted to summarise our learnings as follows.

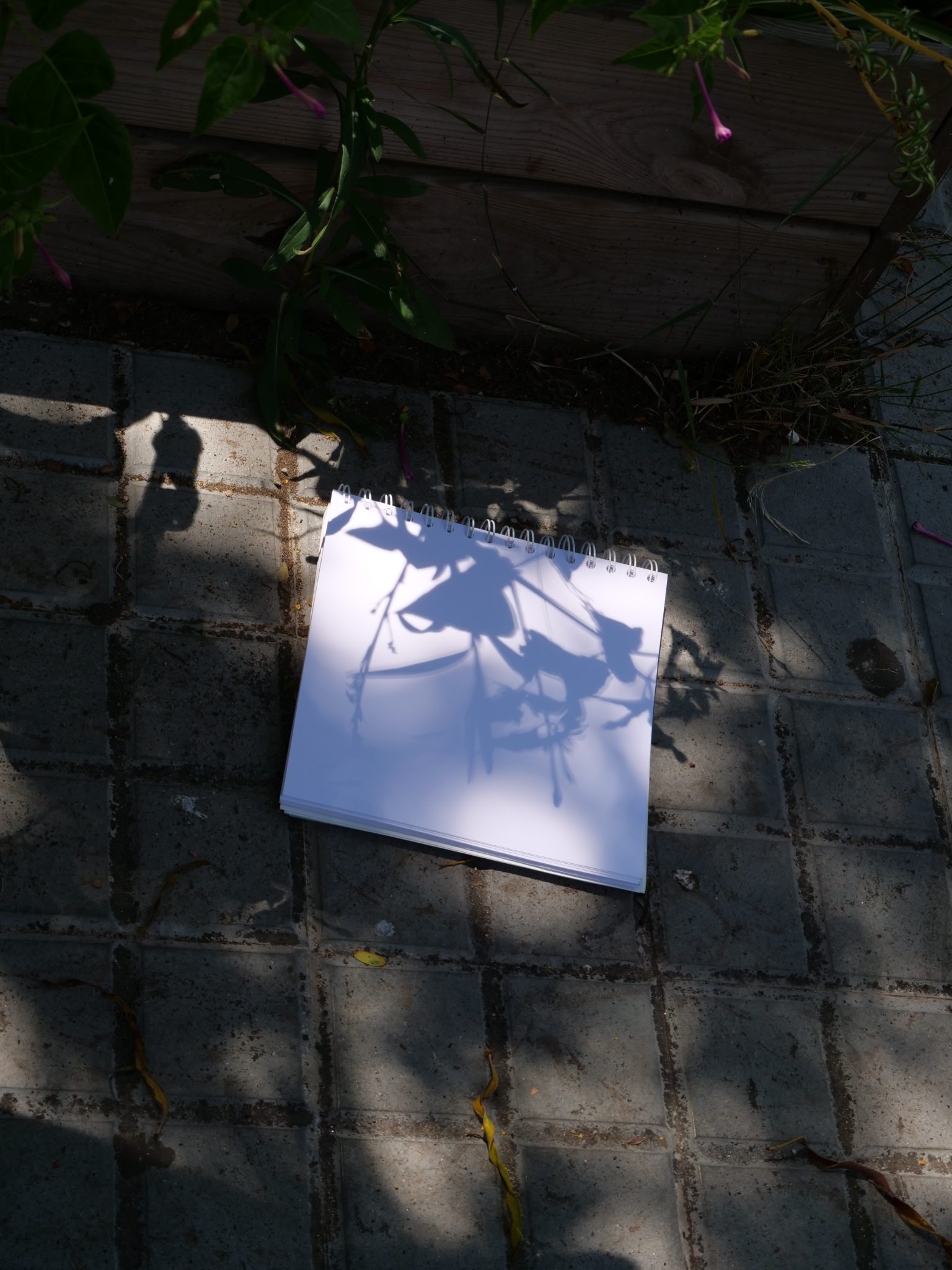

First lesson. To work as an umbrologist, it is advisable not to lose sight of one’s own body, as well as pay attention to the corporeality of our recording materials. Climates are mutating, and so should our recording devices! We learned this together with artist Carla Boserman, who pushed us to try out the complex task of following moving shades with blank pieces of paper, forcing us to go beyond reifying and representational takes. Carla also introduced us to the art of drawing through the climate-prone technique she has been recently exploring: anthotypes on emulsified papers, the predecessor of photographic printing, using the sun as a recording device.

Following shades and their shaky silhouettes, we realized that shades are anything but static. They move, and they move us with them. Also, they are not a single thing but a strange singular amalgamation of contours in between opacity and luminosity. As Carla told us, she became passionate about anthotypes when inquiring on affective forms of inscription that might also be attentive to atmospheric changes [10]: that is, not thought of from pens or pencils that always work, irrespective of the weather they are used in, but from the unstable environmental relationship of the sun imprinting its radiating force on fragile papers.

Second lesson. On our walk through Poblenou, largely inspired by Carla’s work, we realised that it did not make much sense to think of shades as atmospheric occurrences, even though there are many useless, ephemeral or evanescent shadows. Rather, as we discussed at length that same Monday morning, the urban shades that interest us, those that allow us to shelter and cool off, should be thought of more as existential or lived regions.

This was the main result of a collective conversation after spending some time, amazed as well as surprised, debating at length about an intersection. In it, shades were in some way ‘privatized’ by a terrace for the greater part of the day, leaving the nearby playground untouched, turned into an accidental grill for risk-prone parents and children. This ‘regional gaze’ at shades, as someone aptly called it in our discussion, also meant understanding them not from their metric spatial dimensions or climatological indicators but as interwoven topologies of atmospheric care for a plurality of bodies: territories plotted by power relations, flows of movement and knowledge, and divisions enacting sometimes profoundly unequal conditions of access, or as locales of possible multispecies inhabiting [11].

Visiting the locations of the municipality’s shade prototypes, we realized that, in addition to thinking about their patterns or modularity, we always needed to pay attention to: their surroundings, the habitual and possible uses of space, and the modes of circulation, the symbolism and the affordances of given places; and to actors both human and other than human (doves, seagulls, dogs and parakeets being regular companions in our walks). That is, to the different ways in which different actors make these spaces existential territories of life, both in the open and in hideouts, in different moments of the day as well as in the dark hours of the night. This regional, domain-specific look, attentive to the places and their shady life, felt to us of the utmost importance given that the prototypes could redefine and alter urban care: both opening up conflicts that didn’t exist before, hardening others that were hidden, as well as enabling newer ones to emerge.

Third lesson. This corporal approach and the importance of a regional perspective had as a result a full revamping of the kit we had proposed, developing new sheets and protocols of analysis of and intervention in the shades. Also, thanks to the fabulous interventions of Isaac Marrero-Guillamón [12] and Fernando Domínguez Rubio [13], we started imagining different mediational mandates for what a DoU might wish to respond to, drawing from the work of different artistic and activist forms of research they suggested us to resonate with.

As a result of all of these intense 5 days, the zine we worked on materialized a handful of activities to activate a possible DoU, enabling a bunch of research modalities that could be mobilized in different contexts of use.

iii. Prototypes for a DoU: Imagining a future practice

All in all, what these learnings prompted us to reflect on is the poetic and political potential of shades, which transcends the idea of simple technical solutions to thorny problems. In our workshop, shades appeared as a popular and well-spread figure of everyday climatisation (who can’t create shades, even with their own hands?), whose mundanity might precisely allow re-politicizing climate and weather not as things out there, observed and pinned down by meteorologists or climatologists, but as an urban collective concern, eliciting a broader conversation on how we could learn to live in more protective urban ecologies.

In other words, urban shades could also have the power to renew political ecology, the practice of creating and inhabiting them, unfolding a desire for exploration, play, and doing things with others that might not be so obvious when thinking of conventional forms of climatization grounded on air conditioning or ventilation [14]. Precisely because of its mundane nature, shading – a manual activity [15], a hands-on practice of learning to collectively condition and make a space inhabitable under the sun [16] –subtly but unavoidably challenges the problem of modernist solar urbanism and helps qualify mechanical air conditioning acting as a technology for forgetting the deadly fossil fuel substrate of our ways of living and its role in the formation of our atmospheric conundrums [17].

As a result, this issue of Tarde offers prototypes for a Department of Umbrology: a more grounded tentative proposal, slightly upgrading what we learned in the workshop. The accompanying zine, hence, is a small kit with a series of practical exercises and research devices: on the one hand, there are devices enabling a sensitization to what thinking with shades does to understanding the urban, as a matter of sun inclinations and exposure, or a first attempt at their inventory, documenting their changing features, their uses, and uselessness; on the other hand, we have devices for a more collective analysis of shades as regions with their spatial divisions, a proto-ethology of their human and other than human actors, and a series of prompts to elicit individual and group experiences.

Taken as a whole, these six devices enable us to imagine a future practice for the DoU to continue existing. This might also mean mutating in each place and around particular places and topics [18], for the DoU should not just be a collaborative space to study the urban life of shades but an urban space to enter into generative and fruitful shady relations! [19]

References

[1] With this expression, rather than discussing the use of solar power in urban settings, I refer to the signature modernist hygienist drive to design urban settings for clean air circulation and insolation, as a heliocentric approach to city-making. For more context, see Tarde’s issue #6: https://tarde.info/the-city-of-shades/

[2] The latter define their work as “an exercise in political speculation that different experts make to bring possible futures to the present through fictional scenarios that must be addressed within a limited period of time.”

[3] D’Souza, R., & Staal, J. (Eds.). (2024: 10). CICC – Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes. Rotterdam: Framer Framed.

[4] See https://umbrology.org/bcn2024/

[5] See https://www.barcelona.cat/barcelona-pel-clima/sites/default/files/climate_plan_maig.pdf

[6] See https://bithabitat.barcelona/projectes/ombratge/

[7] Needing to calculate the WBGT (wet-bulb globe temperature) index of thermal stress: a measure of environmental heat as it affects humans,r temperature, humidity, radiant heat, comprising ai and air movement. See, for instance, the calculator of the Spanish Institute of Work Safety and Health: https://www.insst.es/documentacion/herramientas-de-prl/calculadores/estres-termico-indice-wbgt-2023

[8] See Jirón, P. (2011). On becoming «la sombra/the shadow». In M. Buscher, J. Urry y K. Witchger, Eds. Mobile Methods. London: Routledge.

[9] See https://pliegos.net/index.php/en/about/

[10] See Boserman, C. (2023). Solar Drawings: On anthotypes and environmental affectivity. Re-visiones,13. http://www.re-visiones.net/index.php/RE-VISIONES/article/view/529

[11] Something for which I’ve found both Vinciane Despret and Bruno Latour’s territorial musings of great food for thought. See Despret, V. (2021). Living as a Bird. Wiley; Latour, B. (2021). After Lockdown: A Metamorphosis. Polity. For an interesting companion for this kind of territorial thinking, see Aït-Touati, F., Arènes, A., & Grégoire, A. (2022). Terra Forma: A Book of Speculative Maps. MIT Press.

[12] Isaac took us on a tour de force revisiting the inspiring works of a dozen artists exploring modes of representation and collaboration to render practicable different ‘mediational’ possibilities of what the DoU might be or, in his words, “I would wish that a Department of Umbrology could think in recursive cycles of research, relationship, and public interfacing”. To name but a few of the many examples he discussed at length to substantiate this, allow me to select just three, because of the impact they left on some of our conversations: Silvia Zayas’s magnificent collaborative artistic speculation ruido ê, working – by means of a documentary and other media – with oceanographers to expand their sensory registers of subaquatic perception when studying manta rays and sharks; Stephen Gill’s Buried photographic series, a work of photographic remediation of the future transformation of the contaminated soil of the Olympic site in London (a moment where many informal uses of the space were lost) recording scenes of the life of these ‘post-industrial marshes’ with a cheap camera, then burying them images on the ground of the conflict, letting them impact it, thus being a double record of the chemicals in the camera and on the ground; Jessie Brennan’s The Cut, a juxtaposed drawing exploring fragments of the oral history of a neighbourhood from London traversed by a canal, using the canal as the storytelling device.

[13] Fernando discussed the speculative work around fiction that the Crisis Cabinet of Political Fictions and cognate works have sought to render practicable. Discussing at length the relevance of fiction to mould reality, he expounded the different scenarios they had been working on. In his presentation, he advocated for a use of fiction that discloses its own shadows (absences, problems, strange effects), rather than hiding its own productive and speculative engine.

[14] With the wonderful exception of the very inspiring hands-on artistic take to ‘air conditioning’ explored years ago by Iñaki Álvarez and Carme Torrent, inventing a wide variety of exercises whereby the air we breathe and sweat is rendered collectively articulate in given situations by means of “actions and choreographic and climatic situations in which the air can be the main character and a performer”, see https://mercatflors.cat/en/espectacle/salmon-air-condition-2/ (the materials of these sessions, graciously donated by Blanca Callén were of great food for thought when imagining the workshop; my appreciation goes to Iñaki, Carme and Blanca for the long conversation we had on this experience).

[15] For a very graphic exploration of this, see Fernández, M. (2021). Tejiendo la calle. Rua ediciones. This book recounts the story of a community-driven architectural project in the village of Valverde de la Vera (Spain), where villagers have engaged in a process of creating parasols out of recycled plastic, later on deciding collectively where and how to hang them in the hot season. This project beautifully shows how these parasols are not just ways of sheltering from the sun, but the changing fabric of a shady community in the making.

[16] In that sense, shading practices could very well be thought of as the next of kin the embodied approaches to ‘weathering’ proposed by Neimanis, A., & Walker, R. L. (2014). Weathering: Climate Change and the “Thick Time” of Transcorporeality. Hypatia, 29(3), 558-575.

[17] An argument developed at length by Barak, O. (2024). Heat, a History: Lessons from the Middle East for a Warming Planet. University of California Press.

[18] In his intervention, Adolfo Estalella ventured beyond his work on ‘ethnographic invention’ (c.f. Criado, T. S., & Estalella, A. (Eds.) (2023). An Ethnographic Inventory: Field Devices for Anthropological Inquiry. Routledge) to offer ‘diffraction’, an optical concept taken from the work Donna Haraway, as an interesting new way to discuss the different attempts, trials and tribulations of a ‘shady’ ethnographic practice beyond the totalising idea of ‘method.’

[19] What Francisco Martínez referred to, in another of the presentations of the workshop, as a practice of opacity. See Martínez, F. (2024). “Lights out: practicing opacity in Estonian basements.” Etnográfica, 28 (1), 285-297.