▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒ Margherita Tess and Santiago Orrego prepared this issue. Zeynep S. Akinci curated it, and Santiago edited and designed it. ▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒

Cite this article: Tess, M. and Orrego, S. 2025. “Umbrellas and other umbracula.” Tarde 9 (Jan – Feb). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/9HXE7

We close our trilogy on urban shadows by presenting a collaborative number on umbrellas, parasols, canopies, and other personal devices producing minimal shade. The issue has the Japanese city of Fukuoka as its primary site for exploration and Medellín, Colombia, as a location to essay a quick ethnographic exercise using some of the prototypes proposed in Tarde´s numbers 6 and 8.

Content

Fukuoka

How are unshaded spaces lived and traversed in cities at the forefront of urban heating? Southern Japan has a famously torrid climate and infamous statistics regarding dwelling in the summer period. This piece, based on ongoing ethnographical research, explores cultures of shading while moving or standing in sun-drenched grey spaces of Japanese urbanity, especially using umbrellas.

Umbrellas as part of the urbanscape

In the hot summer of 2023, I did fieldwork in Fukuoka in southern Japan. In early June, when high temperatures were hitting for the first time in the year, and later in August, when the temperature would not get down to 35 or 37 °C for several days, a daily concern for citizens was the risk of heat stroke, or in Japanese necchusho, the illness of inner heat. Heat sickness, sunstroke, or heatstroke, simply put, arises when the body is not able to regulate its temperature anymore and overheats, causing medical complications if untreated.

During an interview, an epistemic partner in his seventies told me about his experience traversing too hot urban spaces: “I got a heat stroke on Shoninbashi Street in Chuo-ku, Fukuoka City. It was the first time. If I had 30 minutes, I would have gone into a coffee shop to take a break, but I had 10 minutes until the designated time. It was 2:00 p.m. on August 4, and the asphalt road was much more sun-drenched than I had imagined. There were no benches or shade trees to sit and rest. I felt like I were the main character in Albert Camus’ “L’étranger.” I searched for a place where I could rest my body.”In the context of an unliveable outdoors, made of Camusian-like scorching sun, shading things articulate urban relationships between bodies and the sun, creating portions of space with better climatic conditions. Shading things in increased hot summers mediates our sensorial experience of the city spaces and contributes to keeping bodies in safe conditions. As much as other cities in Japan, Fukuoka inherited what Tomás Criado called Solar Urbanism [1]. Streets often constitute urban spaces, and paths are intended more for air-conditioned cars than walking bodies. In this number, I want to focus on one specific minimal shade: the one of parasols. As Japanese cities overheat, several of my informants rely on umbrellas to maintain their body temperature at a lower state. A shading umbrella, I was told, is a must to avoid heat stroke.

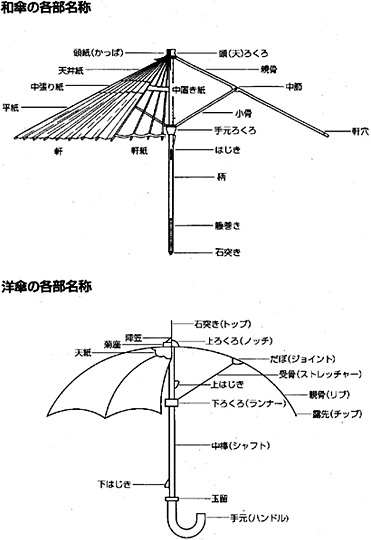

Umbrella, from the Latin umbraculum, literally means small shade. Although umbrellas are most commonly associated with rain nowadays, they carry the original purpose of shading in the name. Today’s higasa (日傘), Japanese parasols, differ from rain umbrellas regarding materials. Although sometimes used interchangeably with rain ones, currently manufactured parasols are specialized in blocking heat and ultraviolet (UV) rays. UV umbrellas include a special coating on the fabric surface made of titanium dioxide, zinc dioxide, or other similar compounds, sometimes black to absorb ultraviolet rays, and sometimes silver designed to reflect UV radiation instead of absorbing it. A quick Google search in Japanese would show thousands of products with different levels of UV absorption and various promises of feeling cooler, protected, and safe. Hundreds of ads show very fair-skinned people looking relieved under pastel color umbrellas.

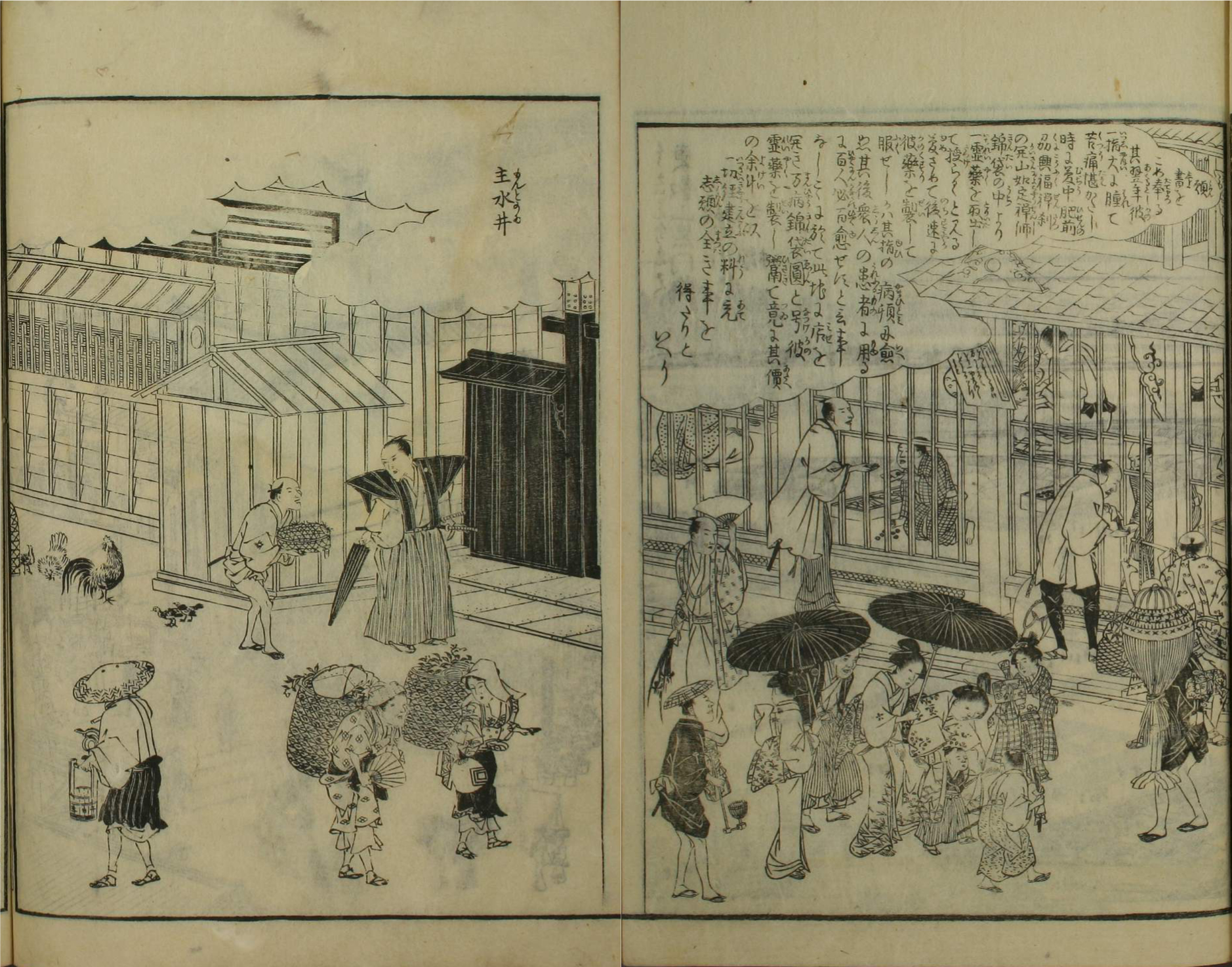

Umbrellas, as shading devices, have a long history. They seem to have existed in Japan since the Kofun period, and during the Heian period, were made of varnished paper and used interchangeably against the sun and rain. However, they were the prerogative of the high classes, while lower class members would wear conical hats. During Kamakura and later the Edo period, they became popular also among Samurai and monks. As portrayed in many wood-print images, umbrellas were part and parcels of the Edo cityscape [2].

The so-called Western umbrellas (yougasa), as opposed to the paper umbrellas (wagasa), were seen for the first time when Commodore Perry arrived in Japan. The yougasa became known in Japan as bat umbrellas (koumorikasa), probably because of their black color and the cloth-made flappy wedges. The bat umbrella rapidly supplanted the Japanese varnished paper one, becoming a symbol of urban Western modernity and refined style.

Today, bat umbrellas might no longer symbolize Western modernity as they did during the Meiji Restoration. However, they are still an essential part of the summer urbanscape and still mediate meanings related to class, race, and urban culture. As scholar Mikiko Ashikari underlines, cultivating a white complexion through shading one’s skin is associated with the urban middle class and mediates colonial ideas of Japaneseness [4]. However, as hazardous levels of heat and sun radiation preoccupy citizens, parasols now also mediate ideas of safety against a dangerous, unshaded environment, which threatens not only the skin but also the healthy thermal regulation of the body. In this piece, I would like to focus on these more recent and under-theorized developments of cultures of shading, meaning the sheltering effect from urban overheating driven by climate change. Borrowing the terms from the previous Tarde issue, I am more interested in umbrella shades as “existential territories of life”, which shelter bodies against a hazardous thermal environment. Heat stroke risk and the fear of suffering from it in public are driving people to use parasols increasingly. Pedestrian crossings, rarely shaded, are traversed by thousands of portable shades, portions of cool microclimates under which human bodies move across solar-centric landscapes. How can this monadic umbracula be conceptualized concerning an overheated urbanity?

Umbrellas and minimal urban spaces

In Fukuoka, as well as other cities in Japan, street trees are a rare luxury. Space in dense cities is precious and expensive, and footpaths are often thin and unshaded. As landscape architects have told me many times, street trees constitute a real issue as they can obstruct the view of drivers, or their fallen leaves and fruits annoy pedestrians and car owners. Often, for several reasons, including low budget for urban greenery maintenance and considering trees a nuisance, street trees are heavily pruned and look more like light poles, depriving them of the shading functions [5]. In this context, minor shading things and devices, such as parasols, create minimal shaded spaces where trees or buildings are unavailable sources of shade. Modern infrastructures and construction that mark the landscape traversed by human and other animal bodies inherit and still are marked by development-centric approaches, where the habitability of the outdoors has passed in the background. Infrastructures and buildings, though, do shade or light as a by-product, allowing for unintentionally shaded spaces, such as under an elevated highway [6]. However, as the thermal environment of Japanese cities overheats, are these shaded byproducts enough? How do citizens negotiate their comfort and safety for the solar design of their urban environment?

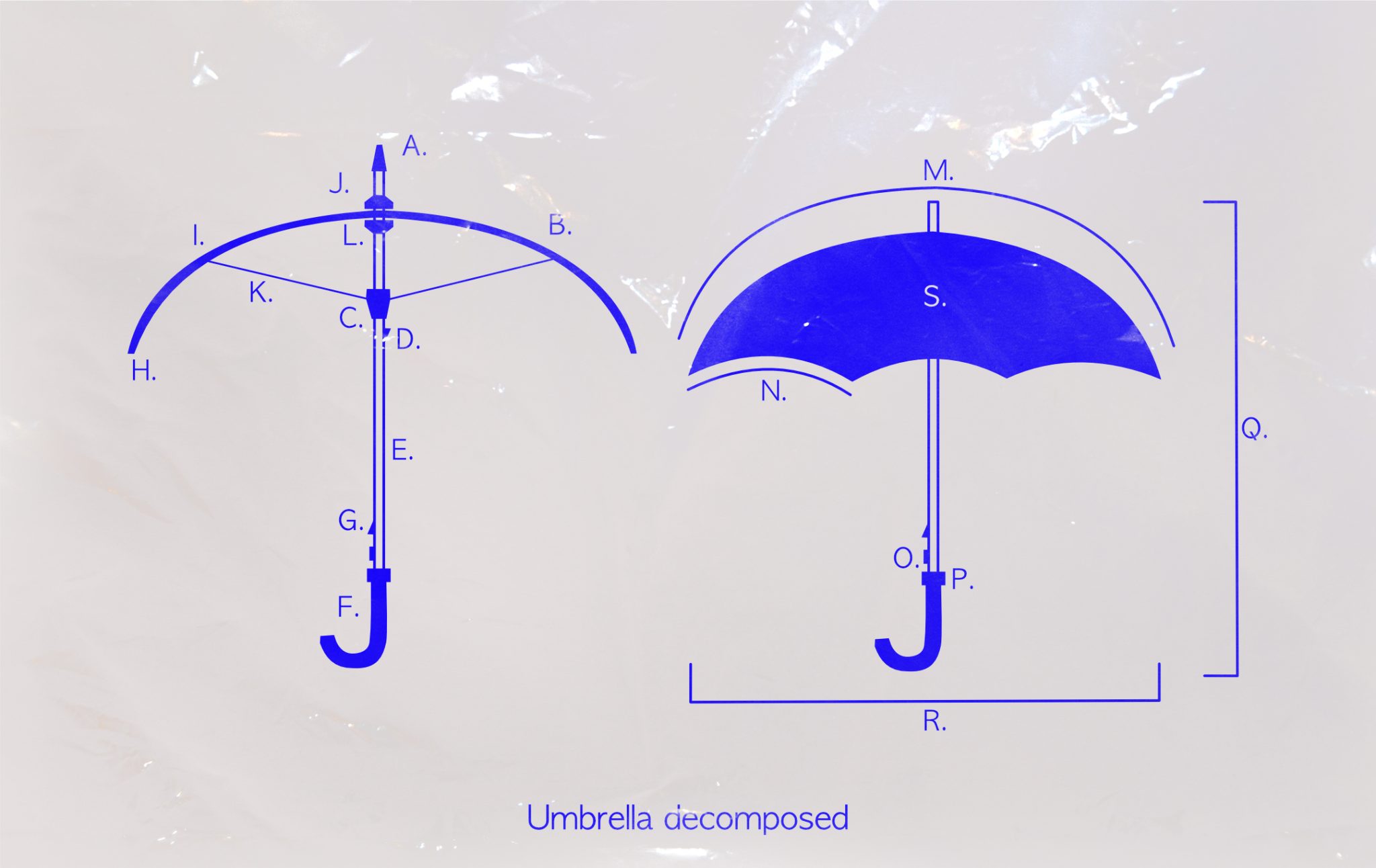

Shades in the context of climate change can be fruitfully explored as ¨lived regions,¨ephemeral but delimited spaces [7]. Although shade appears bidimensional when cast on a flat surface, umbrella shade must be understood as a volumetric region as it creates a tridimensional region of cooler microclimate. A common UV-cut parasol allows for a small portable portion of altered climate: a specific fabric mesh protects the body from ultraviolet rays (responsible for skin damage), and a reflecting or absorbing fabric decreases the temperature, blocking sun radiations’ warming energy. The umbrella poses as a mediator between the sun and the body and is part of a material culture of climatic adaptation. However, the umbrella could also be seen as a spacing device that creates minimal units of inhabitable urban space. If we focus on the space under the umbrella, we can see that it has been critical. Rulers, or gods and spirits in Japanese religiosities, can appear under umbrellas [8]. Not only do gods and rulers exist under the umbrella’s protection, but during rituals or matsuri (shrine festivals), this protected space becomes traversable by lay people. At the Yasurai Festival at Imamiya shrine, worshippers enter under the umbrella to eliminate diseases. Always linked to some form of protection, in some contexts, the space under the umbrella becomes a territory different from the surroundings because of its sacrality; in the current climatic crisis, this shaded portion of space creates a region of microclimatic specificity, differentiating it from a hazardous environment. In other words, the space created by the umbrella, although temporary, elusive, and without clear borders, has been an important and under-theorized urban space.

Designing intentional small shades

In 2021, the Japanese Ministry of Environment published the Climate Change Adaptation Plan. In the section concerning urban spaces, the following scenarios are portrayed: the risk of heatstroke in Tokyo is predicted to increase 2.4 times in the 2050s and, in the 2090s, the time during the day when people can work outdoors in Tokyo and Osaka will be 30 to 40% shorter than at present, and the number of days when it is unsafe to work outdoors will increase. Possible solutions to be implemented include encouraging citizens to stay indoors and pointing to unsafe outdoor environments distinct from sealed and safe indoors. Not surprisingly, shading and its improvement are not considered. Creating and improving public shade is, as this and the previous Tarde numbers have argued, a highly urgent matter. As shown above, umbrellas are crucial shading devices used to traverse overheated urban spaces and cast shaded spaces of cooler microclimates. But, these cast shadows are highly individual spaces in the Japanese case. In this section, I would like to speculate about how intentional public shaded spaces could be designed in overheated urban spaces, taking inspiration from the umbrella’s spatiality. I propose to think with smallness, as suggested by the Japanese architect collective Atelier Bow Wow. The duo often works on and theorizes what they call pet-size spaces. They say that Tokyo’s urban environment is very “infectious.” It spreads fast like a fire and changes constantly [9].

Because of inflationary land prices, they see a “void phobia” in Tokyo, the desire to find and fill any gaps that can be seen. Because of this, items around the size of vending machines are abundant in Tokyo. These items are a bit too small to be recognized as architecture, a bit bigger than furniture, the size that “can exist in the corner of a room, or the corner of the city [10]”. Playing with this format, Bow Wow architects created “Sing and Swing,” a shading device in the shape of a giant balloon that creates a micro-shaded public space exploiting the interstices of the Taiwanese urbanscape [11]. Or, they designed a varnished paper origami refuge. Originally used to create privacy and a sense of safety during disasters in evacuation shelters, it could also work as a shading device [12].

They argue that their design takes advantage of the tiny pet-sized effect and has infiltrated deeply into the city. For them, smallness is a size that allows freedom in urban action. They conclude, “If we consider the abounding pet-sized objects of Tokyo as an interface between the city and the human body, then our urban environment can become more and more comfortable” [13].

Medellín

Umbrellalogy

What I like most about urban shadows—those mundane and opaque figures produced when a random object blocks sunlight—is their playful attitude toward time. As they roam our terrestrial surface, they move gracefully alongside us as we all orbit the sun on our own axes. According to Plato, time is the moving image of eternity [14]. Conversely, shadows —urban shadows— represent moving images of the time-altering and transforming life of the city.

A few months ago, I went on a two-week shadow safari around Medellín, Colombia. As a member of the Department of Umbrology (DoU), I aimed to study shadows’ physical and relational dimensions. However, rather than observing all types of shades, my observations focused on tiny opacities: narrow, volatile, and individual shadows, the portable tools producing them, and the temporal climatic regions generated by them.

For this joint number, the last in the Shadows trilogy, I have prepared a quick and speculative observation exercise inspired by the DoU collective work displayed in Tarde’s numbers 6 and 8. This exercise proposes a topology of tiny opacities and a visual “ethological inventory” to consider shadows as more-than-human climate entanglements and regions of opacity where multiple actors and elements converge.

While in previous explorations, the gaze was on traditional urban locations such as playgrounds, sidewalks, or streets, this issue considers smaller areas that may fit into the “private realm” but that occur and are displayed in the public space of cities worldwide. These areas are temporal shadow-spaces produced under umbrellas and parasols. These urban mobile scenarios appear as a response to the sun, its heat, and the atmospheric and physical sensations it creates. In a rough sense, this exercise could be seen as a spontaneous practice of watching people using umbrellas to escape the scorching sun. And although it may be true, there is also a sort of poetic complexity and reflection behind it.

Why Medellín

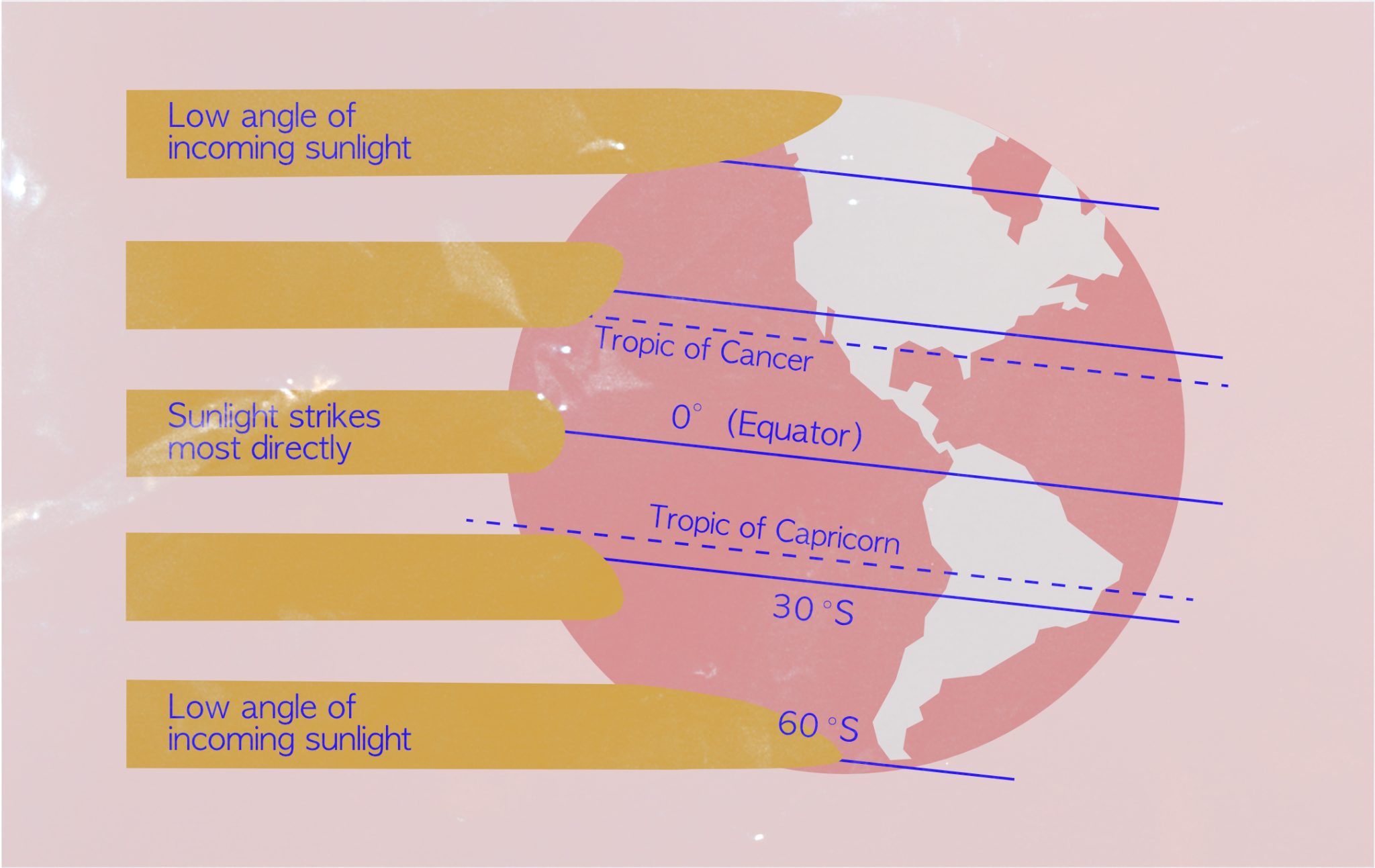

Like all other places on the Equator, Medellín has 12 hours of daylight all year long. That celestial consistency produces a sort of rhythmic stability during the day, but it also makes the sun feel different than at other latitudes. As the picture below shows, the critical relationship with the sun in Equatorial regions happens due to Earth’s spheric shape and the way it is titled. That inclination causes two related phenomena:

- Sunlight hits harder. Because Equatorial cities are closer to the sun than other planetary zones, they suffer from higher temperatures. This situation, mixed with poor environmental planning in urban areas, potentiates urban heat island effects such as heat discomfort, poor air quality, and water degradation.

- UV radiation is more intense. Overexposure to this type of light may cause potential skin damage, such as sunburns and even skin cancer. High radiation exposure can also affect plants and animals in cities.

Additionally, rapid urbanization, which has prioritized cement and concrete over green spaces, and the oversaturation of private vehicles have increased the sensation of heat and suffocation across the city. In areas like Medellín’s downtown or near ample avenues, smog, a lack of public shade, and the already-introduced strong sunlight turn the streets into savage spaces of climate wildness.

Despite the implementation of green corridors, big natural infrastructures composed of native trees and plants around main avenues, or other strategic areas around the city, the intensity of sunlight and UV radiation continues to increase as the actions triggering climate change also increase. As a primary, cheap, old-fashioned contingency method, people rely on umbrellas as first-hand strategies to shelter from the sun.

This rapid exploration hopes to shed some light on those shadow devices and the shadow-spaces they create, bringing them into the discussion and, hopefully, provoking a more robust type of ethnographic exercise that pays attention to shades’ relational nature and crucial role in urban habitability.

A topology of tiny shadows, umbrellas, and canopies

In Medellín, both collective and individual responses to heat and intense sunlight are neither innovative nor different from those in other parts of the world. This exploration aims not to discuss unique methods for facing solar discomfort but to showcase and reflect on a minimal, often personal shade that appears when no other urban shade options are available on the streets. Among many different ways, one could categorize those shades based on their temporality.

First, there are transitory and ephemeral shadows. Created by portable devices like umbrellas—but also hats, sheets of paper, jackets, books, or any other object one might use to create a temporary shadow—this type of shade has a short lifespan. They are generally mobile, although they can also be stationary. An example of this is a person walking under an umbrella, producing a darker, intimate space in motion. This combination of person, umbrella, shadow, and sun creates a momentary pattern on the ground that is instantly displaced as the person walks and the Earth rotates on its axis.

Second, there are stationary and recurrent shadows. They are usually produced by canopies and, to a lesser extent, by awnings. Stationary shadows can also be mobile. They are linked to formal and informal commercial activities. A stationary shadow appears when a person sells goods in a public and open space. It can be anything: street food, clothes, phone cases, lottery tickets, fruits… people tie parasols to the structure they use to prepare, store, or move their products. In that way, parasols protect not only the seller from the sunlight but also their merchandise and, possibly, their clients. It will always depend on the parasol’s size.

The poetics of using umbrellas and canopies

Two people, both wearing red, were waiting for a bus. Although they were simultaneously in the same place, just a few centimeters apart, each was in a different space. The first person, the one near the street, was co-producing and inhabiting a mobile, temporal, and opaque spatiality, a sociotechnical arrangement resulting from the mediation caused by an umbrella between the sun and the person’s body.

As a portable shadow producer, the umbrella spread over their corporality, becoming a flimsy and personal refuge against the piercing and merciless Equatorial sun. Although this device does not have the power to modify the weather, blocking direct sunlight can alter the embodied sensation and perception of the environment and even produce a micro-climate under its spread-out body. This situation makes the experience of being outside at noon waiting for a bus more comfortable.

If one has to point out where the shadow is located, the ground may be the obvious place to look. But is the shadow really there, or is that dark texture just a shade projection? To avoid entering into a Platonic discussion and expanding the figure of regions of opacity, I suggest seeing these types of urban shadows as liminal scenarios ruled by mobile logic.

There are three people and two blue umbrellas; the sun is high and potent above everyone. Their steps are slower and seemingly less coordinated than the other pedestrians. It gives the impression that time passes differently under the tiny, overlapped blue layers. It seems like it also strolls, without hurries, at the shadows’ pace. But shade, in that arrangement, is everywhere and not in a particular place.

However, their liminality is not, this time, in between light and darkness but in between physical and ethereal forms. They are not just projections of a body blocking light; they are spaces that can be inhibited and objects that can be sensed. Once they are opened and facing the sun, umbrellas and canopies unfold a dynamic and sensorial interplay between the body, the object, and the environment. Their shadows can be felt and experienced by walking and going inside and outside them, using our eyes, skin, and whole body.

There is a constellation of microclimates and tiny shade spaces around downtown Medellín. Due to the high rate of informal employment in the city, people are forced to go outside to make a living by providing all types of services and selling all kinds of stuff. In those situations, parasols are everyone’s best friends for spending the entire day outside in an unshaded environment.

Using a canopy (as well as an umbrella) is an act of care to oneself. Notwithstanding, in the case of canopies, caring is extended to other beings and elements: potential customers, a random person looking for temporary shelter while the traffic light changes, and, of course, the goods to be sold. As a stationary type of shadow, parasols also relate differently to the surroundings. They offer a stronger sensation of stability that motivates people to bring furniture to rest.

The sensation of walking surrounded by parasols was a constant reminder that we have never been solar. As our DoU manifesto notes, shades are the very condition of urban habitability, particularly in regions where sunlight is constant and stronger every time. However, what I find more impressive about the massive presence of canopies in public areas of Medellín is their quiet rebellion against the solar hegemony and the harshness of its light. Those extended canopies were inviting us to claim agency over nature and vindicate, as terrestrial beings, our right to opacity. Shall we accept their proposal and join them to be part of the resistance against solar domination?

Footnotes and References

[1] With this expression, the author of a previous number, Tomás Criado, refers to the signature modernist hygienist drive to design urban settings for clean air circulation and insulation as a heliocentric approach to city-making. For more context, see Tarde’s issue #6: https://tarde.info/the-city-of-shades/

[2] For more information on the history of the umbrellas in Japan and theirfer to the iconography, re INAX booklet Kasa.

[3] 江戸名所図会. 巻之1-7 / 斎藤長秋 編輯 ; 長谷川雪旦 画図https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/bunko10/bunko10_06556/index.html

[4] The cultures of shading in Japan are not neutral. Ashikari explores how the Japanese “whiteness” is made and cultivated in opposition to the colonial racial ideas of Ryukyu and Ainu people, but also to colonial Koreans. For a detailed discussion, see Ashikari 2005, Cultivating Japanese Whiteness. More famously, cultures of shading in the Japanese context are associated with the piece by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows. Although Tanizaki’s understanding of shade is slightly different from the ones I am using in this piece, meaning that he is more concerned with design and architectural aesthetics and not much with the actual practice of casting shadows, the piece still has significant ideological overtones. Shaded, demureness, and opacity are elevated as Japanese in contrast to overly bright and flashy Western modernity.

[5] To deepen street tree pruning culture in Japan, see Fujii et al. 2021.

[6] One issue exploring the architecture of infrastructures and their by-product space in cities is Roadsides Collection no.004 – Fall 2020. Architecture and/as Infrastructure. Ed. Madlen Kobi and Nadine Plachta. In this issue, see Light and Space-Making in the Accra Airport City, Ghana, by Naomi Samake (Kobi and Plachta 2020).

[7] See also the previous Tarde number.

[8] Masakatsu Gunji, theorist and anthropologist, has written extensively on the iconography of the umbrella in Japanese culture. He underlines how the space under the umbrella in the Shinto complex can become a microcosm reflecting the macrocosm and how the silk parasol is also important for Buddhist iconography. For a summary of the iconography of the umbrella, see INAX booklet Kasa (Inaxギャラリー名古屋企画委員会 1995).

[9] Tsukamoto, Yoshiharu; Kajima, Momoyo (2006): Atorie wan furomu posuto baburu shiti. Bow-wow from post bubble city. Tōkyō: INAX Shuppan, p. 85.

[10] Kaijima, Momoyo; Kuroda, Junzō; Tsukamoto, Yoshiharu (2021): Made in Tokyo. 17th edition. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd, p. 25.

[11] シング&スイング│Sing & Swing

[設計] アトリエ・ワン [architects] Atelier Bow-Wow

[会場] 台湾実践大学ワークショップ

[location] Taiwan Design Expo 2005

[撮影] アトリエ・ワン [photo] Atelier Bow-Wow

https://www.bow-wow.jp/profile/2005/SingSwing

Page 1

[12] ジャンボ・オリガミ・アーチ・オレンジ│

Jumbo Origamic Arch Orange

[設計] アトリエ・ワン [architects] Atelier Bow-Wow

[会場] 神戸アートヴィレッジセンター [location] Kobe Art Village Center

[撮影] アトリエ・ワン [photo] Atelier Bow-Wow

Page 3

https://www.bow-wow.jp/profile/2005/JumboOrigamiOra/index.html

[13] Kaijima, Momoyo; Kuroda, Junzō; Tsukamoto, Yoshiharu (2021): Made in Tokyo. 17th edition. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd, p. 25.

[14] Chun Lo, Lee (2018): Time, the Image of Absolute Logos: A Comparative Analysis of the Ideas of Augustine and Husserl. Comparative and Continental Philosophy, 10(1), 50–61.