▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒ Jae-Young Lee and Christian Ritter curated this issue. Texts and images: Santiago Orrego ▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒

Cite this article: Orrego, S. 2025. “Watching animals doing nothing. A visual exploration of animal immobilities.” Tarde 10 (March – April). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/5GAHK

Animals are doing nothing

Tierpark Neukölln, 29 September, 2024

A kid is playing with a stick, wielding it like a sword against imaginary enemies. After a while, he begins digging a hole in the ground, removing dirt and grass. A few minutes later, his dad notices the child getting dirty and tells him he should be watching the animals (deer and ducks) instead of what he’s doing. The dad reminds the kid that they are there for the animals. “But, Dad,” the kid complained, “animals are so boring; they’re doing nothing.”

Content

Introduction

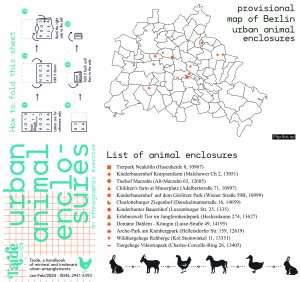

This number returns to Berlin to expand on a topic and a type of space already explored in Tarde’s issue 3: urban animal enclosures. In the mentioned number, I briefly described this kind of location dedicated to human-animal interaction. Then, I proposed a critical analysis that discussed some ethical dilemmas related to animal captivity. Additionally, its printed version displayed a map with twelve animal enclosures, inviting the readers to visit them and conduct a rapid ethnographic exercise that tracked their infrastructures, the beings inhabiting them, and the type of encounters they produced.

For this number, I will focus on two of those spaces: the Kinderbauernhof at Görlitzer Park and the Tierpark Neukölln at Hasenheide Park. Continuing with my work on animal captivity, I intend to visually explore how captivity is produced differently for each type of animal depending on the infrastructures allowing and restringing their motion and encounters with humans and other beings. However, rather than using captivity as an epistemological device to discuss the particularities and arrangements of the animals in those two urban enclosures [1], my goal here is to experiment with one particular condition of captivity that I found fascinating for reflecting on the spatial and relational aspects of the interactions between humans and farmed animals in urban animal enclosures: immobility.

Inspired by Deleuze’s idea of philosophy as the process of creating new concepts [2] and Mol’s empirical-philosophical approach that consists of following how those concepts are “handled in practice” [3], this ethnographic exercise is divided into two parts. First, it will describe the notion of animal immobility through an inventive strategy that mixes Deleuze’s and Mol’s approaches by “using any aspects and components taken from outside, unpacking them as analytical instruments” [4]. Then, once immobility is stabilized as the result of my empirical observations, it will be displayed and materialized in a series of maps that critically reflect on the conditions and degrees of animal immobility.

Stabilizing animal immobility

Urban animal enclosures are locations where people can watch, touch, sometimes ride, learn about, play with, and preserve farmed animals. In those scenarios, animal immobility is a condition of captivity. However, captivity behaves differently depending on the type of animal. This situation produces an incomplete geography of stillness and cohesion, where immobility appears as both an animal condition resulting from anthropocentric managerial logics and desires and an epistemological device that allows us to track and reflect on the ethical and political dilemmas of keeping animals trapped in those human-centered logics. As a device, immobility is constructed by following and enacting material, behavioral, and relational elements.

The Tierpark Neukölln and the Kinderbauernhof at Görlitzer Park are multispecies scenarios composed of fragmented and asymmetrical spaces where farmed animals used to live and be displayed. These spaces are stables, cages, pens, and, in general terms, exhibitions designed to prevent animals from escaping and getting hurt and simultaneously limit and force their contact with humans and other beings. The farmed animals displayed in those urban enclosures are subordinated to anthropocentric managerial logics that control their mobility, food, schedules, and reproduction.

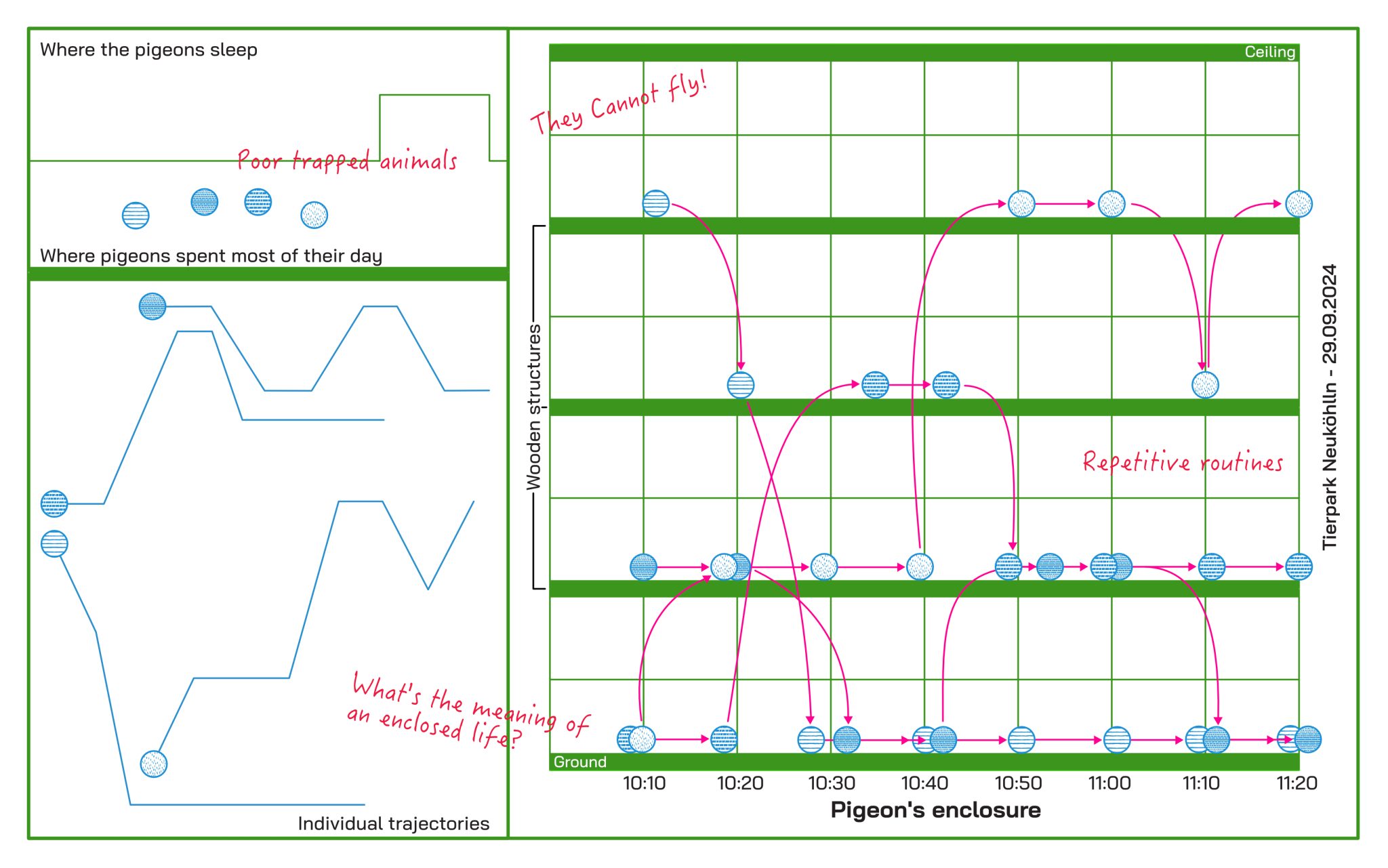

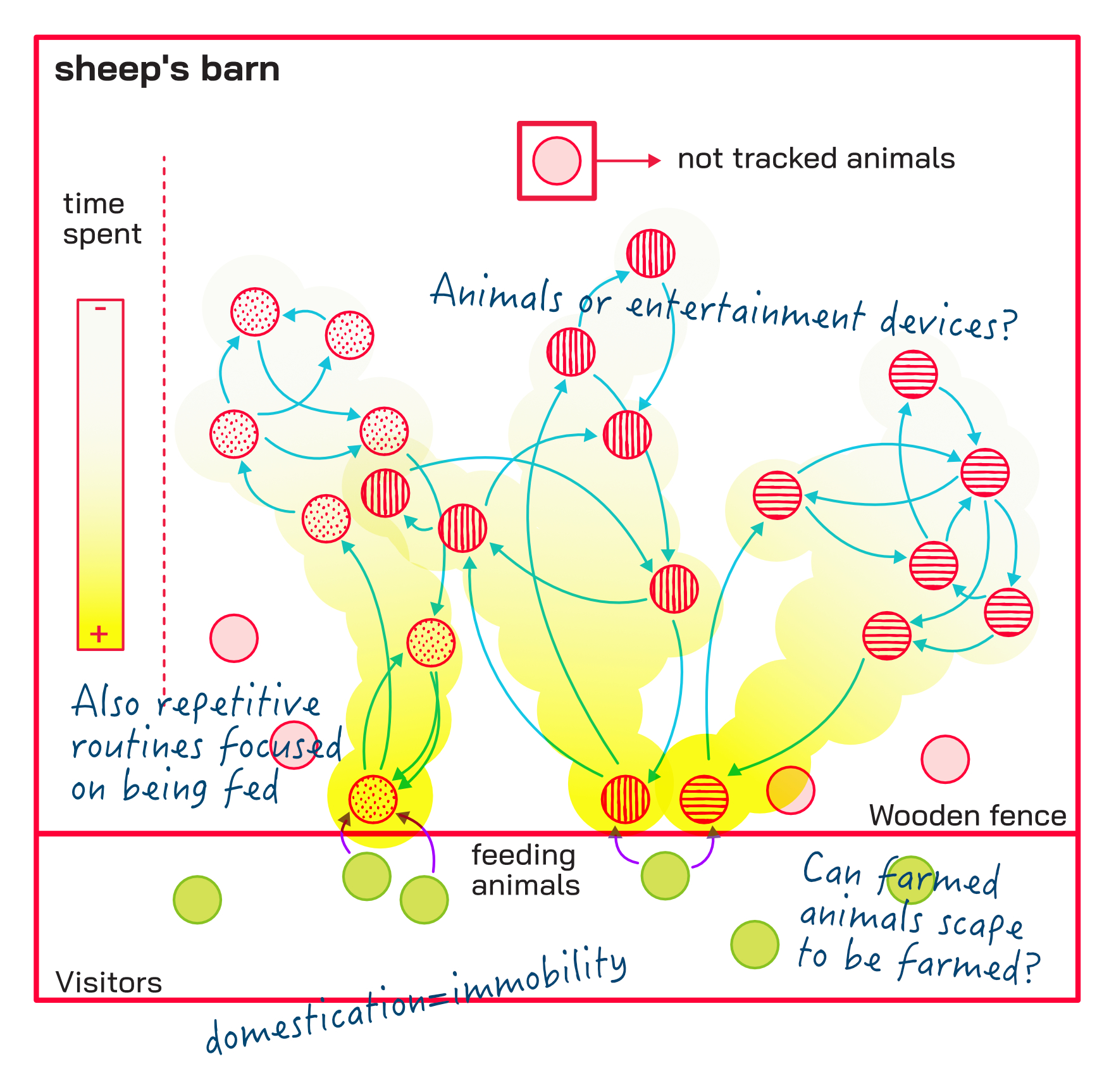

Depending on the type of animal they host, exhibitions may have a more friendly or restrictive infrastructure permitting or limiting human-animal interaction and animal mobility. In the Kinderbauernhof, for example, sheep are displayed inside traditional wooden fences, allowing people to pet and feed them. However, rabbits are locked behind a metal structure that does not permit physical interaction. In the Tierpark, people can touch ponies and donkeys. However, a more restrained infrastructure separates the rest of the animals. For instance, pigeons are enclosed in tiny wooden houses, losing all chances to fly.

Regardless of whether they can interact with human visitors, the animals living in the enclosures are confined to specific, restrictive spaces and stuck in categories such as farmed and/or domesticated. For analytical purposes, the condition of immobility of those animals could be divided into three kinds. First, there is a physical immobility regarding their incapacity to move beyond the limits of their exhibitions. Then, there is a managerial immobility that subordinates them to human decisions that affect their daily lives. Finally, there is an ontological immobility that traps them in ethical and political discussions on how to understand and live with animals that have been domesticated and relegated to farm activities [5]. Shall we keep them captive for their own good? Shall we release them? To where?

Mapping animal immobilities

The maps included in this number are experimental devices created during my field visits and later turned into more appealing visual representations. By paying attention to the physical and managerial components of animal immobility, they attempt to highlight how captivity comes to matter differently depending on the exhibition and the type of farmed animal at the time that —hopefully!— it displays a critical reflection about the ethical, spatial and relational conditions and dilemmas of the urban as a site for multispecies conviviality [6] [7], that, at the same time works as a scenario where “other ‘natures’ are still slaughtered, bred, traded, confined, raced, tested on, put to work, abused and killed” [8].

These devices offer a different approach to animal immobility. The first map displays a vertical representation of how pigeons live in the Tierpark. Caged in a small wooden house, the animals are limited to a reduced space that first and foremost caters to human voyeurism in disregard of animal subjectivities. They can indeed move, but only in the area people have designed for them. What is the point of living a behind-bars life? Should the approach(es) of the urban as a multispecies realm perpetuate colonialist and exploitative anthropocentric perspectives?

The second map shows an interesting case of immobility in sheep based on a human-animal interaction linked to people feeding them at the Kinderbauernhof. The animals spent a lot of time near the wooden bench being fed or waiting to be fed by people. Observing this case, I was interested in reflecting on the relationships between domestication and immobility. People were not feeding the sheep to keep them alive; they were doing it for entertainment because that was a funny activity. On the other hand, the domesticated sheep impressed me because of their presence; they were there, without the choice to do something else or to be somewhere else, just for people to have a good time watching, petting, and feeding them.

The final maps were the saddest ones. I visited the Tierpark more than 40 times in nine months, and lamas were always there. They were enclosed in a tiny space, a small portion of the whole exhibition—three, four, or five lamas altogether. Their reduced space contrasted with the vast green area inhabited by nobody. I was irritated any time I passed by, but they seemed resigned and disturbingly quiet. I left the Tierpark immediately after finishing that map and never went back. Meanwhile, the animals remained there: exhibited, trapped, displayed as entertainment and learning devices, and trapped in infrastructural and anthropocentric immobility.

Pigeons’ house

Tierpark Neukölln

This map shows the movements of pigeons inside the wooden house where they are kept in captivity. The map is composed of three parts. The top left part offers an overhead view of the house. Roughly, this structure is divided into two spaces: (1) a more private area where the animals spend the night and eventually go during the day, and (2) the house’s “front side” where people can see the animals through a metal net. The most significant part of the map displays the enclosure from the perspective of a person looking at it from the outside. This portion of the map shows the pigeons’ movements vertically and horizontally. Their enclosure is composed of wooden structures at different heights, and my work was to track their repetitive mobility patterns going up and down in that reduced space. At the bottom left, the last part of the map isolates each pigeon’s trajectory to have a better look at them.

Sheep’s barn

Kinderbauernhof at Görlitzer Park

This map tracks sheep’s movement and interactions with humans. Sheep are mainly motivated to move to obtain the food people offer them. However, once they are near humans, they remain immobile, waiting for something more to eat while people pet them. I used a “heat map” strategy to observe the places where the animals were most active. The darkest color indicates the places where more time is spent.

While the pigeons’ enclosure made me reflect on immobility as physical cohesion, my experience watching sheep led me to a deeper reflection on domestication as a procedural and multigenerational form of immobility. Yes, sheep remained still waiting for food. Still, the type of steadiness observed here (and non-exclusive to sheep) went beyond a form of immobility caused by spatial and architectural barriers. Domesticated animals are trapped in a never-ending pattern of dependence, work exploitation, and obedience. Some call this “mutualism,” but I see it as plain and straightforward colonialism.

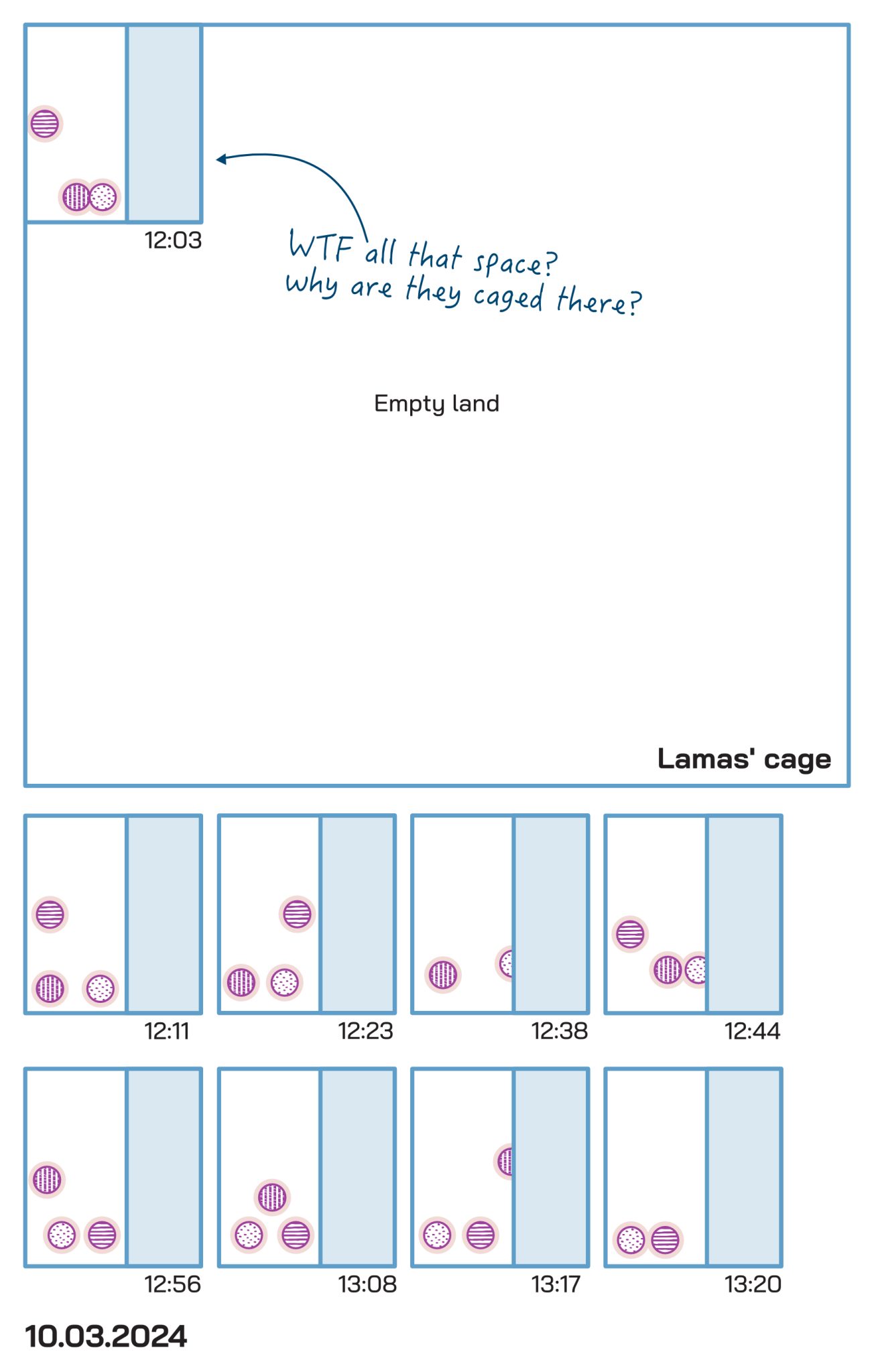

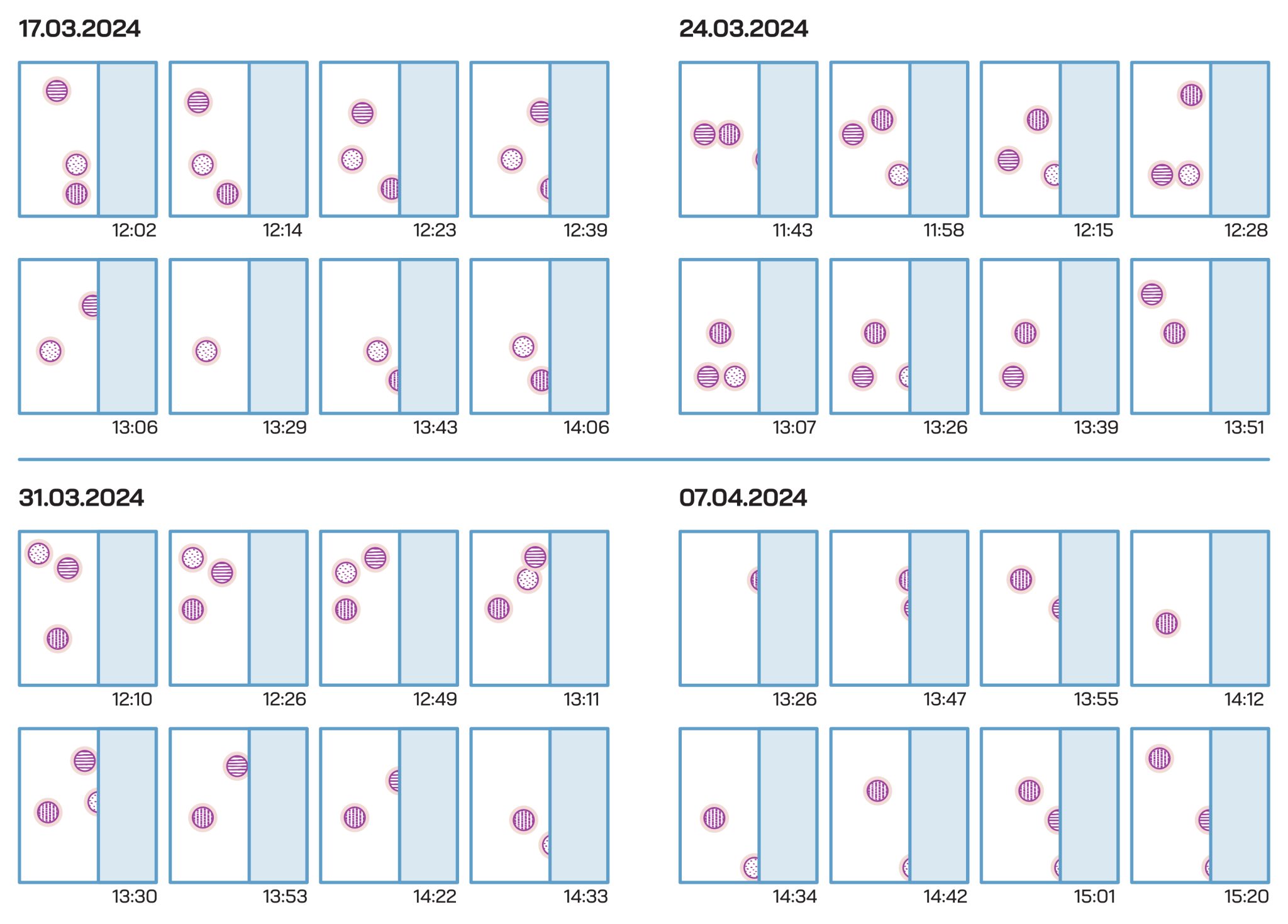

Lamas’ cage

Tierpark Neukölln

Lamas are from the same continent as I am. Nevertheless, unlike me, the lamas inhabiting the Tierpark have never been to South America. They were bred on a farm in Europe. Lamas are more prominent than sheep, however. Despite their enclosure also having a vast empty green area, these animals were always inside a tiny space, smaller than the sheep’s. For farmed animals living in animal enclosures, captivity is presented with different degrees of physical and ontological immobility.

The mapping Lamas exercise consisted of five pieces resulting from situated observation. Although more animals could have been in the cage, I focused only on three. Although I kept the same pattern to identify the animals, that did not mean I always followed the same three animals in each exercise. Overall, this activity had two purposes: (1) To display the spatial difference between the area where those animals used to spend their days and the adjacent empty land that is also part of their enclosure. (2) To highlight the repetitive patterns of mobility that occur in a state of immobility.

Although these maps were designed as overhead representations, I always watched the lamas from the side and through two metal fences.

References

[1] Orrego, S. 2024. “Partial Encounters: Exploring More-Than-Human Entanglements in Berlin’s Animal Enclosures.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography: 1-28.

[2] Deleuze, G. 1994. What is Philosophy? New York: Columbia University Press.

[3] Mol, A. 2002. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham: Duke University Press.

[4] Orrego, S. 2022. “Turning a Traffic Light into an Epistemological Device: An ANT Proposal to Disassemble and Stabilize Urban Life into Regions of Usefulness.” Social Epistemology 36(6): 748-758.

[5] Jones, M. 2021. “Captivity in the Context of a Sanctuary for Formerly Farmed Animals.” In Gruen, L. (Ed.) The Ethics of Captivity. p.p. 90-101. Oxford University Press: New York.

[6] Rigby, K. 2018. “Feathering the Multispecies Nest: Green Cities, Convivial Spaces.” RCC Perspectives 1: 73–80.

[7] Houston, D., Hillier, J., MacCallum, D., Steele, W. and Byrne, J. 2017. “Make Kin, not Cities! Multispecies Entanglements and ‘Becoming-World’ in Planning Theory.” Planning Theory: 1-23.

[8] Arcari Paula, Fiona Probyn-Rapsey, Haley Singer. 2021. “Where Species Don’t Meet: Invisibilized Animals, Urban Nature and City Limits.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4 (3): 940–65.