▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒ Louise Rondel and Laura Henneke prepared this issue. Photos: Laura Henneke and Álvaro Márquez Fernandez. Design and edition, Santiago Orrego ▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒

Cite this article: Rondel, L. and Henneke, L. 2025. “Redundant infrastructures: Exploring, questioning and imagining other possibilities.” Tarde 11 (May – Jun). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/3Z7QU.

Editor’s note: This number resulted from an ethnographic exercise led by Laura Henneke and Louise Rondel, in which a group of ten people explored the socio-material entanglements and contradictions of a car-centered infrastructure in Berlin. After such a fantastic walk, we decided to turn that experience and their reflections into a zine, discuss the notion of redundant infrastructure, and provoke further urban explorations worldwide.

Content

- Introduction: Infrastructural Explorations

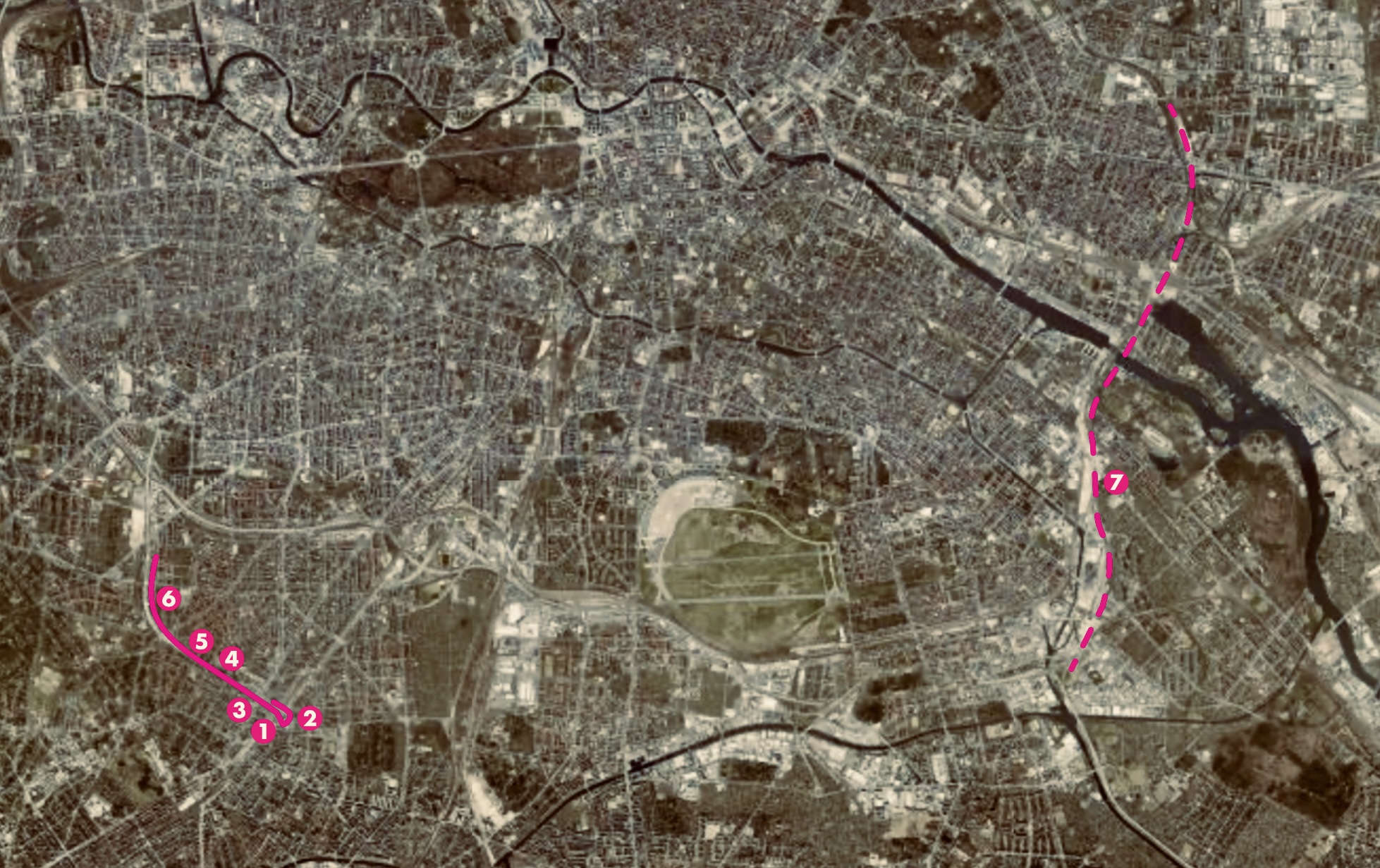

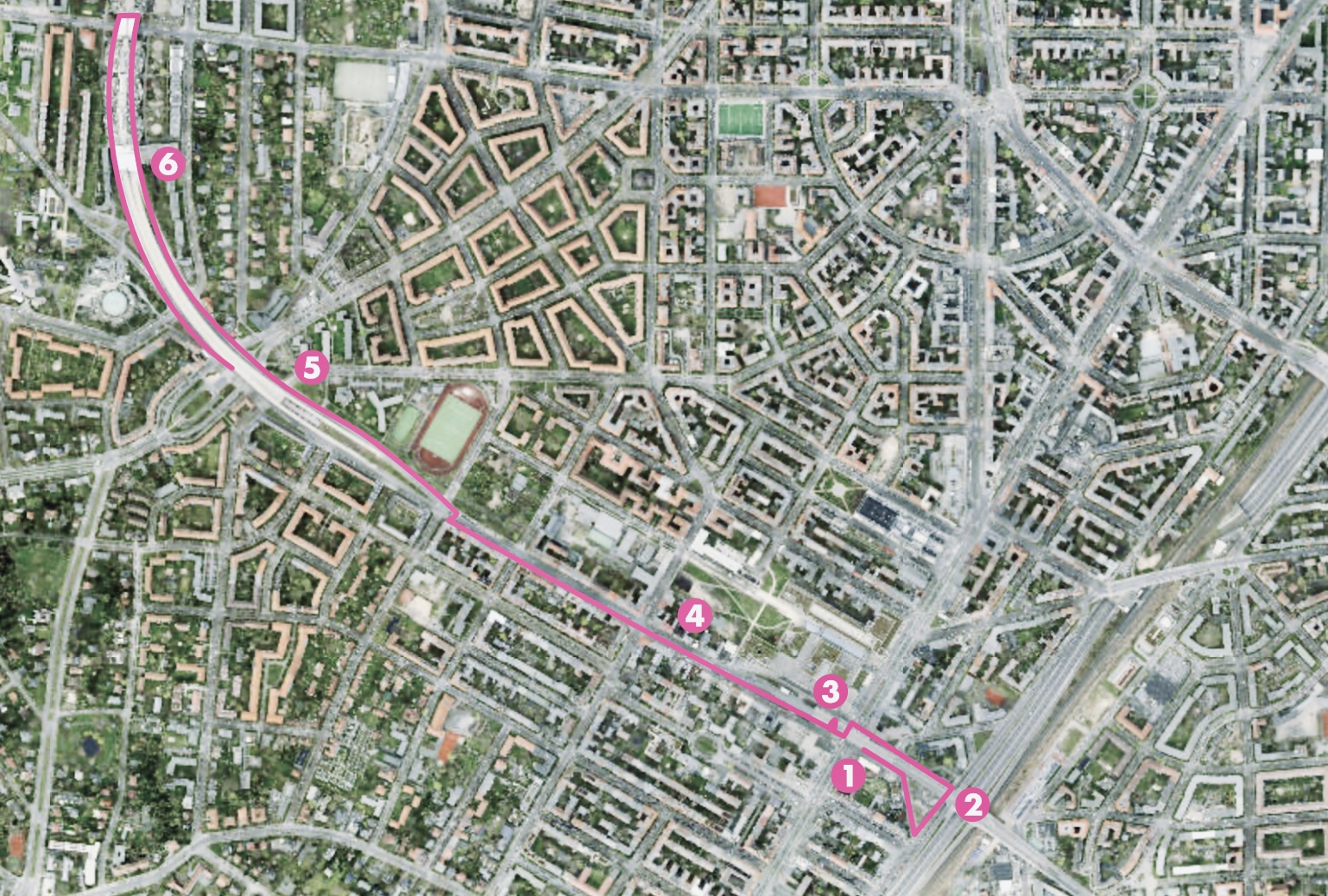

- Walkshop: From the Bierpinsel to the Schlangenbader Tunnel

- The route: A step-by-step guide

- A visual exploration

- Mapping encounters and possibilities

- Handbook references

Introduction: Infrastructural Explorations

Infrastructural Explorations is a series of urban walkshops co-founded by Louise Rondel and Laura Henneke in 2018 in London. Wanting to get out of the classroom, in these walkshops, we invite participants – members of the public, researchers and students – to join us in walking through the city, tracing different forms of urban infrastructure and critically engaging with their impacts on the landscape. As part of the series, we have walked along the River Thames, hunted for above-ground clues to the London Underground, visited municipal- and volunteer-run public libraries, and followed household rubbish to the incinerator and recycling plant. We have also walked around the canals of Castlefield in Manchester, taken DeWaterbus along the Scheldt in Antwerp passing oil refineries and cargo ports, and carried out an infrastructural scavenger hunt over Zoom during the pandemic.

In November 2024, we facilitated a walkshop in in Berlin-Steglitz, walking adjacent to and along infrastructure built for highways that never were. We finished our walk in the Schlangenbader Tunnel, recently closed to undergo repairs affording a pedestrian experience of the wide, smooth asphalt of the highway leading to it, usually solely for motor vehicles. As we walked, we considered the (car-centric) futures that were imagined when these infrastructures were built, what it feels like to be a pedestrian in an auto-landscape, how they have been made redundant, and the other futures which are possible, how they could be (made) non-redundant again to enable different ways of living in cities.

In the following we present our walk through this part of Berlin, from the Bierpinsel to the Schlangenbader Tunnel.

Walkshop: From the Bierpinsel to the Schlangenbader Tunnel

‘Out-of-place: Redundant infrastructures and walking in auto-landscapes’

Date: Thursday 14th November, 12:00 – 15:00

Starting location: U Bahnhof Schloßstraße

The route: From the iconic Bierpinsel into the Schlangenbader Tunnel

Information for participants: Focusing on urban landscapes designed for driving and contestations to this ideal of the car-centric city, this walkshop will explore out-of-placeness – both highway infrastructures that were redundant before they were ever used and how it feels to be a walker in places built for cars. In an exercise in opening our sociological imaginations to the city, this is not a guided tour but rather an open and experimental collective exploration. We invite participants to attune to their bodily and emotional experiences in the places through which we walk, to allow our conversations to be prompted by what we encounter and to be open to the unexpected and happenstance. In connecting our ‘personal troubles’ to ‘public issues’, together we will reflect on how these embodied and affective encounters with the auto-infrastructure can attune us to questions of infrastructure’s social life, the politics of its siting, urban power dynamics, distributional (in)justice and forms of (infra)structural violence. We also consider how this out-of-placeness alerts us to questions of the future of auto-landscapes, in particular in the current context of plans to extend Berlin’s A100.

The walk will be approximately four kilometers, with the pace set by participants. The terrain is paved with a variety of textures. It includes several flights of stairs which can be circumnavigated if necessary. Otherwise, the walk is generally flat with some slopes and may be uneven in places. It will involve walking along and crossing busy roads. There is a public toilet along the way.

Documenting the walk: Participants are invited to contribute to a shared Padlet as we walk. Please upload any reflections, images, sound recordings or videos onto the map.

The route: A step-by-step guide

Step 1: Start at U Bahnhof Schloßstraße

We start at street level of the Schloßstraße underground station, right under the Joachim Tiburtius Bridge in Berlin-Steglitz. The air is thick with the smell of sewage. Above us looms the Bierpinsel, a futuristic but now somewhat neglected landmark designed in the 1970s by architects Ralf Schüler and Ursulina Schüler-Witte – also responsible for Berlin’s iconic ICC exhibition centre. Unlike many underpasses, the space in which we meet is actively used, following the architects’ vision, although it remains defined by the oversized infrastructural imposition above. Oversized because it was planned as a six-lane motorway running straight through the neighbourhood. More on this later. People pass by with shopping bags, waiting at the bus stop or pausing to buy a sausage from a stall. In winter, the open space under the bridge is visited by the Suppenbus on Tuesdays. Volunteers serve a hot meal and tea from their van to people who wouldn’t otherwise get it. Schloßstraße, Steglitz’s main commercial artery, unfolds around us, lined with the well-known brands and department stores typical of German shopping streets.

From here we start walking eastward, following the underside of the bridge but remaining at street level, searching for the quickest route to the staircase that will take us up onto the Joachim-Tiburtius Bridge. Behind the toy store, we circumnavigate the multi-storey car park. To reach the staircase, we must navigate around it and cross Düppelstraße.

Step 2: Joachim-Tiburtius Brücke

Düppelstraße offers an unusual urban scene. One side is lined with Berlin’s characteristic turn-of-the-century tenement buildings, but the opposite side is simply not-existent. Instead of housing blocks there is a roaring six-lane motorway with additional two-lane slip roads, with the S-Bahn tracks running parallel. In the 1960s, this side of Düppelstraße was sacrificed for a 4.2 km long stretch of motorway, a high-speed corridor of noise, pollution, and ceaseless movement.

We take the stairs up to Joachim-Tiburtius Bridge to oversee the large infrastructural damage on the neighbourhood. When approaching the staircase, it feels like walking right into the roaring traffic. Talking to each other becomes difficult and the sense of safety is diminished by lorries and cars that pass right next to us. The escalators are out of order, encased in a makeshift coffin, the staircase is dark and smells of urine. It leads to a small sheltered platform between two motorway slip roads. Built as a stop for an express bus network, it has no obvious function today, but is a good example of the redundant infrastructure that was intended as part of Berlin’s inner-city motorway network, initiated in 1910. Construction started during the Nazi regime, but it was in the period after the Second World War, when East and West Berlin underwent significant urban expansion with a strong trend towards car use resulting in major transformations of important arterial roads. Despite the extensive destruction of Berlin’s urban fabric during the war, planners did not hesitate to demolish intact buildings to accomplish the vision of a car-friendly Berlin. As a result, city streets and squares were transformed into motorways and traffic junctions.

Alarmed by such dramatic changes, citizens mobilised to protest against the completion of plans to build the so-called Westtangente. As part of a wider network, this motorway would have ploughed northwards through the districts of Schöneberg, Tiergarten and Moabit. The historic protest movement was successful and the larger vision of Berlin’s inner-city motorways was never completed. Nor was the construction of a transverse link from Joachim-Tiburtius Bridge – where we are now standing – to Breitenbachplatz. If it wasn’t for the protesters, the connecting Schildhornstraße would have suffered the same fate, losing one of its rows to the wrecking ball, repeating the dramatic cut that had already reshaped Düppelstraße.

Consequently, the Joachim-Tiburtius Bridge became redundant before it ever fulfilled its intended function—a monument to an urban vision that was never fully realised and now feels oversized. The speed limit on the bridge is reduced to 30 km/h. However, the layout of the road is like a motorway, inviting drivers to speed. On the day of our walkshop, we watch the police conducting speed checks, stopping cars that cannot resist the urge or that simply feel entitled to drive faster when they lose the sense of being in a dense urban neighbourhood when they are lifted above street level.

With no choice, we take the stairs back down to Düppelstraße and head back to the iconic Bierpinsel to climb another flight of stairs – a short distance for cars, but a complicated and zigzagging one for pedestrians, and the opposite of an accessible route.

Step 3: Bierpinsel

The tower, nicknamed Bierpinsel (beer brush), was opened in 1976 as a restaurant with great views of what would have become a massive knot in Berlin’s motorway system. The tower is structurally integrated into the Joachim Tiburtius Bridge. The building, which is visible from afar in Steglitz, is part of pop architecture, which is reflected not only in the unusual polygonal shape of the tower, but also in the orange-red colour scheme. Next to the tower is the stair tower, which houses the steps for the ascent. After a café moved out as the last tenant in 2010, the tower stood empty and is in need of renovation following water damage. However, the current owner is not working on the listed building and instead the immediate space around it is falling into disrepair.

We go back down the stairs and turn right to walk west along the ramp of the Joachim Tiburtius Bridge. The space under the landing is used as a car park. Decorative details in this otherwise uninviting space remind us that the structure is part of the overall design by the architects Schüler-Witte, which includes the Bierpinsel Tower, the Joachim Tiburtius Bridge and the space underneath it, as well as the Schlossstrasse underground station. We walk along buildings with shop fronts occupied by inconspicuous shops, take-out restaurants or service providers. It dawns on us that the monstrous ramps prevent walk-in customers from turning into the side street of the large Schlosstraße with its shopping. On the other side of the ramp stretches the naked façade of the ”Boulevard”, a giant inner-city shopping mall with mostly vacant retail space. Same as the motorway, it feels out-of-space and oversized in this neighbourhood.

Step 4: Schildhornstraße

Following Schildhornstraße for the next 500 meters is a typical walk along a main street in Berlin. If we had walked here two years earlier, we would have been surrounded by much heavier traffic. Schildhornstraße, which was once intended to be a motorway, nevertheless served the purpose of a cross-connection between two inner-city motorways and thus led to very heavy traffic congestion. The result was one of Berlin’s most polluted streets, a congested corridor of noise and exhaust fumes cutting through the neighborhood.

The relief came with the closure of the Schlangenbader Tunnel which will mark the end of our walk. Traffic has been rerouted elsewhere, and Schildhornstraße feels almost uncharacteristically quiet—an unsettling reminder of how drastically the flow of urban life can change with a single infrastructural decision.

Step 5: Breitenbachplatz

Breitenbachplatz lies in front of us but instead of a square we see another relic of Berlin’s unfinished highway network: oversized, underutilized ramps redundant in their function yet still dominant in their physical presence. Instead of efficiently guiding traffic, they create a deep cut in the square, isolating different parts of the neighborhood, turning what could have been a cohesive public space into a fragmented, car-dominated landscape.

We find the ramps blocked off with construction site fencing. From here we walk with a special permit from Berlin’s Civil Engineering Department. Walking up the ramps makes you feel small. A person on a roadway makes you feel small and powerful at the same time. Their smooth asphalt is dotted with the droppings of rabbits. These animals must feel even smaller.

Step 6: Schlangenbader Tunnel

The ramps lead to the Schlangenbader Tunnel – a bold experiment in urban planning. Built in the late 1970s and early 1980s, die Schlange (the Snake) is the only residential building in the world constructed directly on top of a fully enclosed autobahn. Over a thousand apartments sit above the 1.7-kilometre tunnel, an attempt to combine infrastructure and housing in cramped West Berlin. Today, however, the tunnel is in need of serious repairs, forcing the city to close it down. It also raises the question of redundancy: was this street ever truly needed as a major traffic artery, or was it simply a byproduct of Berlin’s overbuilt road network?

The sudden closure has disrupted established traffic patterns, but it has also exposed an uncomfortable truth: the tunnel itself may be as redundant as the ramps at Breitenbachplatz. Its function as a major traffic corridor has been largely absorbed by other routes, and its role as a residential experiment remains an outlier in urban design.

People briefly reclaimed the closed Schlangenbader Tunnel, turning the eery space into an impromptu playground for street art, underground events and makeshift hangouts. But the city soon intervened, fencing off the entrances and installing surveillance cameras to prevent further trespassing.

These sites—Schildhornstraße, Breitenbachplatz, and the Schlangenbader Tunnel—stand as reminders of Berlin’s layered urban history, shaped by ambitious infrastructure projects, shifting transportation policies, and the persistent tension between mobility and neighborhood life. Yet they also reveal something else: the redundancy of much of Berlin’s car-oriented infrastructure. Projects once seen as essential now exist in a limbo between obsolescence and preservation, leaving behind spaces that are neither fully functional nor fully reclaimed by the city.

Step 7: A100 extension: A future auto-landscape

This issue is particularly relevant in light of the ongoing expansion of the A100 urban motorway in eastern Berlin – a project still based on century-old plans dating back to 1910. Despite decades of research into traffic management, urban planning and climate change, the Berlin Senate continues to push ahead with this mega-project, which experts warn will not reduce congestion, but instead encourage more car traffic. In addition, the new section – particularly the controversial 17th phase – will once again cut through intact neighbourhoods, displacing residents, businesses and cultural spaces. The redundancy of this extension is striking: with Berlin’s recent budget cuts halting most investment in public transport, cycling infrastructure and climate-friendly transport alternatives, doubling down on car infrastructure seems increasingly out of step with the city’s long-term sustainability goals. Rather than solving mobility problems, the A100 extension risks becoming an expensive relic of outdated planning ideals.

We debate these thoughts while standing under the looming concrete landing of Schlangenbader Tunnel, a structure soon to be torn down, causing dust and noise in the neighborhood for at least two years. And then what? The demolition will close one tear in the urban fabric, but the ongoing A100 extension to the east threatens to open a new one. As the city dismantles parts of its past, it continues to build new infrastructure that divides neighborhoods and perpetuates car-centric planning, repeating the same mistakes in the name of progress.

A visual exploration

Mapping encounters and possibilities

As we walked from the Bierpinsel into the Schlangenbader Tunnel, we used a shared Padlet to document what we encountered as well as our emotional and embodied experiences and reflections. We recorded both moments of out-of-placeness and other ways in which infrastructures can be lived, and posted what we saw, heard and felt on a collective map. Our responses are testament to what it feels like to walk in an auto-landscape – ‘it’s so LOUD’ – but also what other forms of sociality might be possible.

Handbook references

[1] Amin A. (2014) Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society 31(7–8): 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414548490

[2] El-Enany, N. (2019) Race, law and the air we breathe. Paper presented at Contemporary Conversations: Carceral Continuum, Nottingham Contemporary. https://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/whats-on/contemporary-conversation-carceral-continuum/

[3] Evans, A. (2024) Road As: A journey up the A13, against the A13. Printed at Rabbit’s Road Press: London.

[4] Lowbridge, C. (2025) Snake Pass: Could famous road close to cars?. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c5yrnz5wxgko

[5] Rondel, L. (2024). ‘Fighting for breath’: Inhabiting uninhabitable places. European Journal of Cultural Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494241284639

[6] Rondel, L., and Henneke, L. (2024). Walking the (infrastructural) line: Mobile and embodied explorations of infrastructures and their impact on the urban landscape. Sociological Research Online.https://doi.org/10.1177/13607804241247713

[7] Neimanis A and Phillips P (2019) Postcards from the underground. Journal of Public Pedagogies: WalkingLab 4: 127–139.

[8] Mills CW (1959) The Sociological Imagination. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.